Bulletin – June 2019 Financial Stability A Decade of Post-crisis G20 Financial Sector Reforms

- Download 537KB

Abstract

The global financial crisis resulted in significant disruption to markets, financial systems and economies. It also led to comprehensive reform of the financial sector by the G20 group of countries. After a decade of policy design and implementation, standards in the global financial system and regulatory approaches in many countries have changed substantially to improve financial system resilience. Australia, as a G20 member, has been active in implementing these reforms. This article looks at the main financial sector reforms developed in the immediate post-crisis period, their implementation in Australia and the more recent shift in international bodies' focus to assessing whether these reforms have met their intended objectives.

Introduction

Following the onset of the global financial crisis (GFC) just over a decade ago, the G20[1] and key international bodies, together with authorities in individual countries, embarked on a broad-ranging reform of financial sector regulation and supervisory frameworks. The reforms were intended to have a medium- and long-term focus, to address the vulnerabilities and regulatory gaps revealed by the crisis.

The initial post-crisis focus of the G20, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) and global standard-setting bodies (SSBs)[2] was on four core reform areas: building resilient financial institutions, mitigating the ‘too big to fail’ problem, and addressing risks in both over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives markets and the shadow banking sector. Substantial reforms were developed in each of these areas, with timelines set for implementation. There were also many reforms beyond these core areas, such as macroprudential frameworks and tools, credit rating agencies and accounting standards.

More than a decade has passed since the peak of the crisis. This article looks back at the G20 financial sector reforms, with a particular focus on their implementation in Australia.[3] It also looks ahead, as the international community has more recently shifted its focus to evaluating the effects of the reforms to assess whether they are meeting their objectives. This evaluation work is likely to continue to feature prominently on the financial reform agenda in the coming years.

The Different Stages of the G20's Post-crisis Policy Response

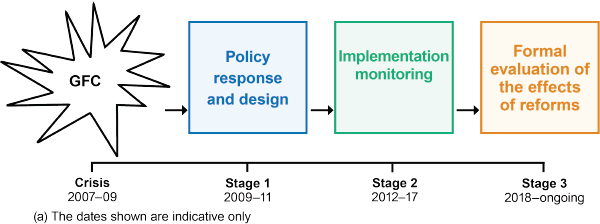

The post-crisis policy response by the G20 can be broadly thought of as having three overlapping stages (Figure 1).

Crisis Response – Changing Priorities(a)

Sources: RBA

The key elements of each stage are discussed below.

Stage 1: Policy response and design. Globally, in addition to restoring confidence, the immediate post-crisis response was to identify the sources of the problems that led to the GFC. After identifying these root causes, international bodies worked on the design and release of important elements of the core reforms. The process began with the G20 Leaders statement of 2009 heralding a sweeping set of financial reforms. This was followed by the development of specific key reforms, discussed in more detail below, to give effect to the G20's broad vision.

Stage 2: Implementation monitoring. As reforms and new standards were developed and published, they typically came with implementation timetables, which often stretched over several years. To help ensure the full, complete and timely implementation of the reforms, SSBs embarked on a detailed monitoring program to review the adoption of the reforms across countries. Each SSB generally monitored the implementation of their own standards.[4] However, the FSB had a major overall monitoring role. Its Coordination Framework for Implementation Monitoring followed progress in the adoption of the core G20 reforms, while an associated Implementation Monitoring Network (IMN) tracked progress in other reform areas. The results of this ongoing monitoring are summarised in the FSB's annual report on the implementation and effects of reforms (first issued in 2015), as well as in the FSB's jurisdiction-specific annual updates on implementation. The former report mainly covered implementation monitoring, but it also conveyed the initial work by the FSB on assessing the effects of the reforms. This early FSB work on the effects of reforms was to an extent limited, likely reflecting the fact that sufficient experience with many reforms had not been gained as they were only just beginning to be implemented during this period.

Stage 3: Formal evaluation of the effects of reforms. As policy design and implementation has progressed, the G20, FSB and SSBs have shifted their focus towards assessing the effects of the reforms, to determine whether they are meeting their intended objectives. Using a formal evaluation framework released by the FSB in 2017, the first two formal evaluations were completed in 2018. Another key aim of the evaluations is to identify unintended material consequences of the reforms that may need addressing. These are to be assessed by the SSBs that developed the relevant policies, to determine whether a policy response is required.

These stages were, and are, overlapping. For example, during the implementation monitoring stage of the early Basel III reforms, policy design work continued on finalising aspects of the Basel III capital reforms (which were not completed until the end of 2017). And, in Stage 3, the evaluation work is being conducted while implementation monitoring is ongoing. But the stages give a broad sense of how the priorities of the international bodies have evolved through time. Key features of these stages are discussed in more detail below, with the Stage 2 discussion focused on Australia.

Initial Post-crisis Policy Response

The GFC led to an almost unprecedented disruption to financial markets and systems, as well as having significant negative effects on the real economy, including a large drop in output and falls in international trade.[5] As described in Schwartz (2013), the scale and breadth of disruption prompted a comprehensive post-crisis response from the G20. The initial effort centred on the four core areas of reform noted earlier, with each involving a range of policy actions (Table 1). This focus, particularly on bank resilience and the risks posed by systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs), reflected the immediate vulnerabilities exposed by the crisis. The core reforms are discussed below, with a particular focus on developments in recent years (see Schwartz (2013) for a more detailed summary of the earlier reforms).

The first core reform area was ‘building more resilient financial institutions’. The failure or near failure of many banks highlighted the inadequacy of banks' capital and liquidity buffers. This prompted a major rewrite of global banking standards by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) in what has become known as the Basel III reforms, which were released in 2010. These focused on significantly increasing the quality and quantity of capital held by banks, and enhancing the liquidity resilience of banks (both over short horizons with the 30-day Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), and over the longer term, with the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR)). These reforms also included a constraint on overall leverage to complement the risk-based capital requirements. Further changes were agreed at the end of 2017. These changes sought to address the significant variation in the value of risk weights calculated by banks, even among those with similar business models and risk profiles. This issue had been revealed by the BCBS's monitoring of Basel III implementation. A key change was that banks that use ‘internal models’ to calculate regulatory capital requirements must hold at least 72.5 per cent of the capital that they would hold under the ‘standardised approach’ (using parameters set by the regulator), even if their models suggest a lower amount of capital.

Another element of the building resilient financial institutions reforms related to compensation standards. This reflected the view that excessive risk-taking by financial institutions had contributed to the crisis, which, in turn, had been partly driven by remuneration and wider compensation practices that rewarded such risk-taking. Moreover, these practices tended to reward short-term results, with limited scope to punish poor outcomes over the medium or longer term. In response, the FSB developed its Principles for Sound Compensation Practices and their Implementation Standards, which aim to align employees' risk-taking incentives with the risk appetite and long-term profitability of the firm, particularly at significant financial institutions. Notably, the standards recommend the ability to claw back part of employees' (unvested) remuneration at a later date.

| Area | Lead bodies(a) | Key elements(b) |

|---|---|---|

| Building resilient financial institutions | BCBS (banks) IAIS (insurers) FSB |

|

| Ending ‘too big to fail’ | BCBS, CPMI, FSB, IAIS, IOSCO |

|

| Making derivatives markets safer | BCBS, CPMI, IOSCO |

|

| Addressing risks in shadow banking | BCBS, FSB, IOSCO |

|

|

(a) BCBS = Basel Committee on Banking Supervision; CPMI = Committee on

Payments and Market Infrastructures; FSB = Financial Stability Board;

IAIS = International Association of Insurance Supervisors; IOSCO = International

Organization of Securities Commissions Sources: BCBS; CPMI; FSB; IAIS; IOSCO |

||

During the crisis, authorities in numerous countries were called upon to bail out banks and other financial institutions using public funds, thereby exposing taxpayers to potentially large losses and generating moral hazard.[6] These actions were taken because the disorderly failure of such institutions, due to their size, complexity or systemic interconnectedness, would have caused significant difficulties for the wider financial system and broader economy. That is, the institutions were ‘too big to fail’. Addressing this problem was the second core reform area, with global bodies taking a range of actions:

-

The FSB introduced a framework for addressing the risks posed by SIFIs in 2010, with an early focus on global SIFIs (G-SIFIs), as their failure can affect multiple countries. The following year, the FSB outlined a suite of more specific G-SIFI policy measures. A key element was a new resolution standard, the Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions (Key Attributes).[7] The focus on effective resolution regimes reflects the goal of avoiding the severe costs of financial institution failures as seen during the crisis. Reducing (if not eliminating) the need to use public funds to support stressed financial institutions became a goal of international bodies and several individual jurisdictions.[8] Other G-SIFI measures included higher loss absorbency requirements as well as establishing networks of supervisors to cover banks operating in several jurisdictions (cross-border supervisory colleges) and crisis management groups for these institutions.

While the initial focus of implementing the Key Attributes was on banks, in recent years, global efforts have focused on applying them to insurers and financial market infrastructures (FMIs), such as central counterparties (CCPs), with additional guidance specific to these sectors.

- In parallel with the FSB's broad SIFI policy work, the BCBS and the IAIS developed methodologies for identifying banks and insurers that were ‘clearly systemic in a global context’.[9] Lists of global systemically important banks (G-SIBs) and insurers were first published by the FSB in 2011, and 2013, respectively.

A subsequent key development in the effort to address the ‘too big to fail’ problem is the FSB's 2015 total loss-absorbing capacity (TLAC) standard for G-SIBs. The standard is intended to ensure that G-SIBs can be resolved in an orderly way by requiring G-SIBs to have a minimum amount of TLAC, which is composed of both regulatory capital and other eligible debt, with the latter able to be ‘bailed in’ (that is, written down or converted into equity). The minimum TLAC requirement will be phased in from 2019, reaching 18 per cent of risk-weighted assets (RWAs) when fully implemented by 2022. G-SIBs headquartered in emerging market economies (EMEs) have extra time to meet the requirements.

The third core reform area relates to OTC derivative markets. The crisis showed that the complex network of OTC derivative exposures between financial institutions made it difficult to monitor concentrations of risk and greatly increased the scope for contagion. As a result, in September 2009, the G20 leaders agreed that ‘all standardised OTC derivative contracts should be traded on exchanges or electronic trading platforms, where appropriate, and cleared through central counterparties by the end of 2012 at the latest. OTC derivative contracts should be reported to trade repositories. Non-centrally cleared contracts should be subject to higher capital requirements.’ The goal of mandatory central clearing was to replace financial institutions' bilateral derivative exposures with a single net exposure to a CCP, thereby simplifying the network of interconnections and reducing total exposure. In addition, a series of reforms were introduced for those OTC derivatives that are not centrally cleared. For these trades, under 2013 reforms, financial institutions are required to exchange collateral (in the form of margin) to reduce the risks associated with these contracts.[10] In 2015, standards were also issued on risk mitigation techniques for non-centrally cleared derivatives. Collectively, these reforms aimed to provide incentives to centrally clear OTC derivatives trades, and to ensure that the risks associated with non-centrally cleared trades were effectively recognised and managed. The combined effect of the reforms to promote increased use of central clearing also had the effect of concentrating risks in CCPs, which led to global efforts to enhance their regulation and resilience as discussed below.

Financial institutions and activities outside the formal banking system, such as money market funds (MMFs) and securitisation, amplified both the build-up of vulnerabilities before the GFC and the ensuing financial instability. As a result, the fourth core area of reform addressed ‘shadow banking’ risks. Early reforms focused on MMFs, securitisation, shadow banking entities other than MMFs, and securities financing transactions (SFTs) such as repurchase agreements (repos) and securities lending. Subsequent reforms have focused on addressing structural vulnerabilities in the asset management sector (namely redemption run risk and leverage), and the risks posed by shadow banks to the banking sector. In terms of the latter, capital requirements for banks' equity investments in funds have been tightened, with banks required to apply risk weights to the underlying exposures of a fund as if the exposures were directly held. Guidelines on ‘step-in’ risk have also been issued. These seek to mitigate the risk that banks, to avoid reputational damage, ‘step in’ to support unconsolidated but related entities (such as MMFs and other funds) which could transfer financial distress to the bank.

Financial Sector Reforms beyond the Core Areas

Beyond the four core reform areas, international bodies and national authorities have also made substantial reforms in other areas. The FSB's IMN monitors 10 broad areas of other post-crisis G20 financial sector reforms, with numerous individual elements within each category (Table 2). These reforms cover different types of financial institutions and markets, as well as multiple areas of regulatory and supervisory practices and standards.

| Area | Specific elements |

|---|---|

| Hedge funds |

|

| Securitisation |

|

| Enhancing supervision |

|

| Building and implementing macroprudential frameworks and tools |

|

| Improving oversight of credit rating agencies (CRAs) |

|

| Enhancing and aligning accounting standards |

|

| Enhancing risk management |

|

| Strengthening deposit insurance |

|

| Safeguarding the integrity and efficiency of financial markets |

|

| Enhancing financial consumer protection |

|

|

Source: FSB |

|

These non-core reforms involve a mix of (ongoing) improvements to existing standards or regulatory approaches (such as improving deposit insurance schemes (DISs) or enhancing consumer protection) and addressing perceived gaps in the pre-crisis regulatory framework that were exposed by the GFC. There are several key examples of the latter:

- A focus on reforms related to securitisation reflects the fact that the early stages of the crisis centred on structured products involving securitisation. There was considerable uncertainty about the quality and value of asset-backed securities and the assets underlying them. In addition to potentially misleading ratings being applied by credit rating agencies (CRAs) – which prompted a separate reform effort (discussed below) – these products had inherent risks due to misaligned incentives. For example, in securitising assets off their balance sheets, many financial institutions did not accurately assess or monitor the risks that were being transferred, because they had no financial interest in the securitised assets, i.e. no ‘skin in the game’.[11]

- The work on enhancing macroprudential frameworks reflects the view that, before the crisis, banking sector regulators had a mostly microprudential focus. That is, regulators focused excessively on addressing the risks posed by individual institutions. In doing so, they largely missed the build-up of broad-based, systemic risks posed by the collective activities of multiple financial institutions, such as in the US subprime housing loan market. This failing required an expanded focus, to include macroprudential policymaking and tools to address systemic risks, either by establishing new bodies for that purpose or assigning macroprudential goals and tools to the existing regulator(s).

- The CRA reforms were, in part, triggered by concerns that the very high credit ratings assigned by CRAs to many structured products (such as collaterised loan obligations) contributed to the crisis. In hindsight, these ratings were overly optimistic and led to the actual risk of those products being underpriced, which fuelled their marketing and sale, adding to the pre-crisis build-up of risk within the financial system. The GFC also highlighted the scope for conflicts of interest, as CRAs were being remunerated by clients who would benefit by receiving higher ratings for their financial products such as debt securities and structured products. Such incentives were seen as jeopardising the independence of CRA's analysis.

Australia's Implementation of the G20 Financial Regulatory Reforms

As members of the G20 and the FSB, and of the SSBs, Australia's main financial regulatory agencies (those on the Council of Financial Regulators (CFR)) were able to contribute to the policy design discussions that led to the main reforms agreed in Stage 1.[12] The agencies' objective was not only to achieve good policy outcomes, but also to bring Australia's perspective and domestic circumstances to the discussion and, where appropriate, build in a degree of flexibility and proportionality for the adoption of global standards domestically.

Australia was not as badly affected by the GFC as were many other economies, especially those in the north Atlantic. For example, Australia's banks remained profitable with capital ratios comfortably above regulatory minimums as asset quality was relatively resilient. At least in part, this reflected the effectiveness of the domestic regulatory and supervisory framework, with local bank rules that were ‘super equivalent’ to (i.e. stricter than) global standards. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) for example applied more conservative definitions of capital than the international standard.[13]

Even though Australia was not as severely affected by the crisis as many other economies, nonetheless, Australian authorities implemented many of the core global financial sector core reforms, as required of G20 members (Table 3). As noted by Schwartz (2013), Australia adopted these global reforms as there was room for improvement within Australia's domestic arrangements and there were lessons to be learnt from international experience. Meeting or exceeding the new global standards also assured investors, both domestic and overseas, that Australia's regulatory framework would continue to evolve to match best practice. It was also in Australia's interests to demonstrate a commitment to new standards and to support the ‘level playing field’ provided by global standards. As financial markets are global in scope, regulatory weaknesses in one or more jurisdictions can contribute to systemic risks, and lead to regulatory arbitrage and an associated decline in prudential standards. Adherence to global standards by Australia and other countries helps make the global financial system safer.

| Global reform (and implementation date where applicable) |

Australian implementation (with Australian variations) |

|---|---|

| Building resilient financial institutions | |

| Basel III Capital | |

| Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1): 3.5% (2013) → 4.5% (2015) |

4.5% (2013)(a) |

| Capital conservation buffer (CCB): 0.625% (2016) → 2.5% (2019) |

2.5% (2016)(a) |

| Leverage ratio 3% original exposure definition (2018) revised exposure definition (2022) |

Internal ratings-based approach banks: proposed 3.5% (2022) Standardised approach banks: proposed 3% (2022) |

| Basel III Liquidity | |

| Liquidity Coverage Ratio 60% (2015) → 100% (2019) |

100% (2015)(a) RBA Committed Liquidity Facility (2015) |

| Net Stable Funding Ratio (2018) | 100% (2018) |

| Ending ‘too big to fail’ | |

| G-SIB higher loss absorbency: 1.0-2.5% (2016 → 2019)(b) Additional requirements(c) |

Not applicable (no Australian G-SIBs) |

| D-SIB higher loss absorbency (2016 → 2019) | D-SIB (2016)(a) – 1% CET1 add-on for major banks |

| TLAC: 16% (2019) → 18% (2022)(d) except for G-SIBs in EMEs: 16% (2025) → 18% (2028) |

APRA loss-absorbing capacity proposals (2018): – additional requirement of 4–5% of capital for the four major banks – proposed implementation by 2023 |

| Making derivatives markets safer | |

| Greater use of central clearing (2012) | Mandatory central clearing regime for OTC interest rate derivatives denominated in AUD, USD, EUR, GBP and JPY (2016)(e) |

| Reporting of trades to trade repositories (2012) | 2013 (initially for major financial institutions) |

| Margin requirements for non-centrally cleared trades (2016 → 2020) | 2017 → 2020 |

| Addressing risks in shadow banking | |

| Mitigate risks posed by shadow banks |

Enhanced capital (2011) and risk management requirements (2017) for managed investment schemes (including retail hedge funds) Reduced ability of finance companies and other registered financial corporations to offer deposit-type products (2014) Powers to address financial stability risks posed by non-ADI lenders (2018) Annual RBA update to CFR on developments in non-bank financial intermediation |

| Repos and securities lending | |

| Evaluate case for a CCP for repos | RBA-conducted review of the costs and benefits of a repo CCP in Australia (2015) |

| Enhancing data reporting standards | New APRA Economic and Financial Statistics data collection includes enhanced data reporting standards for repos and securities lending (to start late 2019) |

|

(a) No phase in Sources: APRA; ASIC; BCBS; FSB; IOSCO; RBA |

|

Of particular note is that, in the immediate post-crisis years, APRA implemented the Basel III reforms often in full and earlier than was required by the BCBS. This was the case with the capital reforms (the Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) and capital conservation buffer requirements) and the short-term liquidity requirement (the LCR). In conjunction with the domestic implementation of the LCR, the RBA introduced a Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF) for qualifying banks. This was necessary because Australian banks would not have been able to meet the LCR with existing liquid assets, due to the limited amount of government debt on issue in Australia. This highlights the flexibility of global standards, which are often minimums or allow national discretion (or use of built-in flexibility) to reflect domestic financial, legal or regulatory circumstances. In discussions on the development of Basel III, the RBA and APRA argued for the inclusion of alternative liquidity arrangements such as the CLF for countries with a limited supply of high-quality liquid assets. The CLF provides eligible banks with access to a pre-specified amount of liquidity, for a fee, through repurchase agreements of eligible securities outside the RBA's normal market operations. As well as implementing the reforms earlier than required, APRA also generally took a more conservative approach than the BCBS standards. For example, APRA did not adopt the Basel III concessional treatment for certain capital items.

In recent years, APRA has implemented further elements of the Basel III reforms. In 2018, in line with the BCBS deadlines, it implemented the NSFR (which was the last remaining key element of the Basel III liquidity reforms). In the same year, APRA also released its plans to implement the Basel III leverage ratio, as well as other revisions to the capital framework to reflect the finalisation of outstanding Basel III capital reforms by the BCBS the previous year.

In Australia, APRA implemented the FSB compensation principles for banks and insurers through a new prudential standard on remuneration in 2010. The key principle underlying this standard is that performance-based remuneration must be designed to encourage behaviour that supports the firm's risk management framework and long-term financial soundness. More recently, the Banking Executive Accountability Regime, which applies to all banks from 1 July 2019, introduces stricter rules on the remuneration of banks' senior executives and directors. In particular, a proportion of variable remuneration must be deferred for at least four years, and variable remuneration must be reduced for accountable persons who do not meet their accountability obligations.

The extensive ‘too big to fail’ reforms applying to G-SIFIs were not directly implemented in Australia as no G-SIFI banks or insurers are headquartered here. However, domestic variants of these global rules have been pursued in many jurisdictions, including Australia.

- There are many cases where banks and other financial institutions, while not having a global systemic footprint, are nonetheless systemic in their local jurisdiction. Australia – like many other small jurisdictions – adopted the BCBS's 2012 domestic SIB (D-SIB) framework, tailored to local conditions. APRA's D-SIB framework was released in 2013, identifying the four major Australian banks as D-SIBs and imposing an additional capital surcharge of 1 per cent of CET1 on each of them.

- The TLAC standard noted earlier explicitly applies to the 30 or so banks identified as G-SIBs. However, like regulators in several other countries, APRA has been working on building a loss-absorbing and recapitalisation capacity framework, to deal with a bank failure or near failure. This is in keeping with a government-endorsed recommendation of the 2014 Financial System Inquiry. APRA released a discussion paper detailing its proposed approach to loss-absorbing capacity for banks in 2018. It proposed increasing the total capital requirement of the Australian D-SIBs by between 4 and 5 per cent of RWAs. While the additional requirement can be met with other types of regulatory capital (for instance, through retained earnings or issuance of Additional Tier 1 instruments), it is expected that this would be mostly met through increased issuance of Tier 2 capital instruments because of its lower cost. This means using existing capital instruments rather than the more novel structural, contractual or statutory approaches used in other jurisdictions to increase the liabilities that can be ‘bailed in’. APRA is expected to release its response to the consultation in mid 2019.

Australian reform efforts in recent years have also focused on resolution regimes. In 2012, Treasury released a consultation paper on expanding APRA's crisis management powers. APRA's powers were ultimately significantly enhanced through new legislation in 2018, so that it can more effectively prepare for, and manage, a distressed bank or insurer, as well as any affiliated group entities. In particular, the legislation clarifies APRA's powers to set requirements for resolution planning for banks and insurers (for example, by issuing prudential standards for resolution and recovery planning, supported by formal powers to direct firms to address barriers to their orderly resolution, such as by changing their business, structure or organisation).

A resolution regime for FMIs is also being developed. In 2015, Treasury issued a consultation paper seeking views on proposals to establish a special resolution regime for FMIs, consistent with international standards (in particular, the Key Attributes). The paper requested feedback in areas such as the scope of the resolution regime, resolution powers such as statutory management, transfer and directions, funding arrangements and international cooperation. The CFR agencies are currently developing detailed designs for the regime, with a further public consultation expected later in 2019.

APRA, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) and the RBA have been working towards implementing the OTC derivatives market reforms since 2009. As with many other G20 reforms, implementation has required strong collaboration between the Australian regulators, largely through the CFR. Based on their joint recommendations, the government required that, from 2016, all Australian OTC interest rate derivatives denominated in Australian dollars, US dollars, euro, Japanese yen and British pounds must be centrally cleared. Reporting of OTC derivatives trades to trade repositories was also required from 2013 for major financial institutions, and from 2014 for other financial entities. APRA has also imposed margin and risk management requirements for derivatives that are not centrally cleared.

Several key global reforms did not have direct applicability to Australia, or were already largely included in existing regulations, and hence were not adopted locally.

-

The shadow banking reforms were adopted to only a limited extent in Australia. The

shadow banking sector is a relatively small share of the domestic financial

system which, under the proportionality built into the FSB's shadow banking

framework, reduces the extent to which global reforms need to be applied.

Further relevant points are noted below.

- Australia already largely met several of the key post-crisis recommendations on shadow banking. For example, IOSCO recommended that constant net asset value (NAV) MMFs should move to a floating NAV where possible; in Australia, most MMF-type funds were already operating on a floating NAV basis.

- A 2016 peer review report by the FSB on the regulation of shadow banking concluded that Australia already had a systematic process to review the regulatory perimeter (which determines the population of financial institutions/activities that are within the scope of regulation and/or supervision).[14]

- There was limited need to change the regulation of repos and other SFTs. Australia's SFT market is relatively small and below thresholds set for implementation of key FSB recommendations (such as applying ‘haircut floors’ on ‘non-bank to non-bank’ SFTs). Several recommendations, however, were followed through. The FSB recommended that authorities should evaluate the costs and benefits of introducing CCPs for inter-dealer repos, where CCPs do not already exist. In 2015, and following a consultation, the RBA assessed the costs and benefits of a repo CCP in Australia and determined that, while under certain circumstances it would be open to a market-led CCP, it would not at that time mandate central clearing for repos. Further, also in keeping with FSB recommendations, Australia adopted enhanced data reporting standards for ADI's and registered financial corporation's repos and securities lending, as part of APRA's modernised ‘economic and financial statistics’ collection (with these entities expected to commence reporting the new data in late 2019).

- The key role of banks in the financial system was a factor in ASIC deciding not to adopt an IOSCO securitisation recommendation, which was to impose mandatory risk retention requirements on issuers. Specifically, ASIC came to the view that bank issuers had sufficient ‘skin in the game’ as servicers of the underlying assets, as well as through entitlements to residual income and brand risk.[15]

- In terms of enhancing macroprudential frameworks and tools, significant changes have not been implemented in Australia. APRA's supervision and analysis of risks already incorporated a system-wide perspective that was less evident in some other regulators. The broader than simply microprudential approach is consistent with APRA's statutory financial stability mandate and arguably helped limit the build-up of vulnerabilities in Australia before the GFC. Moreover, APRA already has an extensive set of prudential tools that it can use for both micro- and macroprudential purposes (in the case of the latter, this was demonstrated by APRA's implementation of housing-related prudential measures in 2014 and 2017).[16] Finally, the CFR agencies have a long tradition of strong cooperation on financial stability matters, reducing the need to establish a new macroprudential body, or change existing arrangements by assigning explicit new macroprudential goals, powers and tools to one or more agencies.

Overall, Australia has demonstrated strong commitment to the international reform effort. It has typically implemented the core G20 financial sector reforms in full, without taking advantage of phase-in periods, along with many of the 22 other G20 policy reforms monitored by the FSB.

The Evaluation of Reforms Is a Key G20/FSB Focus

With the design of the reforms largely complete, and many having been implemented, the G20 and international bodies have started to formally evaluate their effects. This new work aims to determine whether the post-crisis reforms have achieved their intended aims, and whether there are any material unintended consequences that may need to be addressed (without compromising the agreed level of resilience). These evaluations will be a key feature of the financial regulatory work of the G20, FSB and SSBs in the period ahead.

The main evaluations to date are being coordinated by the FSB. The FSB sees the evaluations of the effects of reforms as an important element of its accountability to the G20 and the public. It also informs structured policy discussions among FSB members and SSBs. The first two formal evaluations launched by the FSB and SSBs focused on the effects of reforms on (a) the incentives to centrally clear derivatives and (b) infrastructure finance, with both evaluations concluding in 2018.

- As discussed earlier, the clearing of standardised OTC derivatives through a CCP was a key element of the reforms of OTC derivatives markets. The FSB and relevant SSBs concluded that the changes observed in OTC derivatives markets were consistent with the G20 aim of promoting central clearing, especially for the most systemic market participants. In particular, the capital, margin and clearing reforms combined to create an incentive to centrally clear OTC derivatives, at least for dealers and larger and more active clients. However, it was also found that the provision of client clearing services is concentrated in a relatively small number of bank-affiliated clearing firms. This can make access to central clearing difficult and costly for some smaller clients. The evaluation also found that the Basel III leverage ratio can be a disincentive for client clearing service providers to offer or expand client clearing (discussed below).

- The second evaluation concluded that the effects of reforms on infrastructure finance were of a second order relative to other factors, such as the macrofinancial environment, government policy and institutional factors. No material negative effects of key reforms on the provision and cost of infrastructure finance were identified.

An evaluation is now underway to assess the effects of reforms on financing for small to medium-sized enterprises. In recent months, the FSB launched an evaluation of the effects of the ‘too big to fail’ reforms in the banking sector. It will: (i) explore whether the reforms have addressed the systemic and moral hazard risks associated with SIBs; and (ii) analyse broader effects (positive or negative) on the financial system, such as overall resilience, the functioning of markets, global financial integration, and the cost and availability of financing.

To enhance transparency and rigour, these evaluations will seek a broad range of input and feedback, including from academic advisers and through a public consultation process. Importantly, the FSB envisages adjusting the post-crisis reforms where there is evidence of material unintended consequences. For example, the evaluation on the incentives to centrally clear OTC derivatives found that the treatment of initial client margin in the Basel III leverage ratio calculation may be reducing the incentive to offer client clearing services. This in turn could contribute to the concentration in, or even withdrawal of, client clearing services. The BCBS has since consulted on a targeted and limited revision to the leverage ratio exposure measure to address this issue.

Separate to the evaluation program, international bodies have been conscious of the implications of their promotion of central clearing of OTC derivatives. At the same time that the G20 and SSBs have been working to reduce the ‘too big to fail’ problem, CCPs have emerged as a new set of financially systemic entities, in part due to the reforms. Given their high degree of interconnectedness and their position at the heart of the financial system there is a risk that CCPs could be one possible location of the next financial crisis.[17] International bodies are alert to the financial stability risks posed by CCPs, especially those that operate across multiple jurisdictions. In 2017, the FSB and relevant SSBs identified 12 (now 13) CCPs that are systemically important in more than one jurisdiction. Reflecting these concerns, recent efforts by the FSB, CPMI and IOSCO aim to enhance the regulation and supervision of CCPs, and to increase their resilience and resolvability.[18] In certain jurisdictions, such as the United States, FMIs have been designated as SIFIs, resulting in stricter regulation and supervision.[19]

Another lasting effect of the GFC is that global bodies are especially focused on avoiding a repeat of the huge economic and social costs of crisis by actively looking for, and addressing, emerging vulnerabilities. A key part of the FSB's mandate, agreed in 2009, is that it will assess vulnerabilities affecting the global financial system and identify and review the actions needed to address them. This focus has been emphasised by the new FSB Chair, who stated recently that assessing and mitigating vulnerabilities is ‘the core piece of the FSB's mission’.[20] In addition to assessing current global vulnerabilities (such as high private and public debt), this mandate underpins recent work by the FSB on more medium-term emerging vulnerabilities, often in collaboration with the SSBs. Such work includes assessing the financial stability implications of crypto-assets and financial innovation more broadly, encouraging climate-related disclosures by financial institutions, and building financial sector resilience to cyber-related attacks and risks.

Conclusion

The GFC led to a decade of enormous change in financial regulation and, in turn, the global financial system. Reforms were made across a wide range of areas, with an initial focus on four core areas to address the most prominent vulnerabilities revealed by the crisis. In recent years, global focus has turned to evaluating the effects of reforms, with a view to addressing any material unintended consequences. Australia has embraced these changes, which have made its financial system more resilient. However, as the financial system evolves, including in response to those same reforms, it is inevitable that new threats to financial stability will emerge and authorities will need to remain vigilant.

Footnotes

The author is from Financial Stability Department. [*]

The Group of Twenty (G20) is the main international forum for global economic cooperation, and is comprised of 19 countries (including Australia) plus the European Union. [1]

The key SSBs relevant for the G20 financial sector reforms are: the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS); the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI); the International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS); and the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO). The FSB is an international body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system and, in this context, helps coordinate the policy development work of the SSBs. [2]

In doing so, this article also updates an earlier Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Bulletin article on these themes. See Schwartz C (2013). [3]

The BCBS, in particular, set up an in-depth monitoring and reporting process for the new global banking rules (known as Basel III), as part of its Regulatory Consistency Assessment Programme (RCAP). The BCBS issued its first report on Basel III implementation in October 2011, with semi-annual updates since then. The BCBS's RCAP has two streams. It monitors implementation according to stated timelines, as well as assessing the consistency and completeness of implementation that is conducted on both a jurisdictional and thematic (e.g. liquidity reforms) basis. [4]

These financial and real effects are discussed in a recent speech by the Reserve Bank's Deputy Governor. See Debelle G (2018). [5]

Moral hazard in this context refers to the possibility that, under official regulation and supervision, banks could adopt riskier business strategies, lending and investments in the expectation of a public sector bailout if problems occur, or that depositors and other creditors will be less motivated in regularly assessing the soundness of the bank they lend to. [6]

In terms of a bank, resolution can be seen as the actions by a resolution authority (or authorities) to use available tools to manage a bank in stress in an orderly manner so as to safeguard financial stability (and for other aims such as the continuity of the bank's critical functions and the protection of depositors) with minimal costs to taxpayers. [7]

For example, in the United States, the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act changed the US Federal Reserve (the Fed)'s authority to carry out emergency measures. Under the new law, the Fed must obtain approval from the Treasury Department before exercising its extraordinary lending authority. In addition, the Fed may extend credit only under a program with broad eligibility – it cannot create programs designed to support individual institutions. In the European Union, the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive applies strict limits on when public funds (for example, resolution funds) can be used in resolution. [8]

For more on the assessment methodologies for identifying G-SIFIs, see Yuksel M (2014). [9]

Margin reduces two risks: it prevents the build-up of exposures as prices and interest rates fluctuate each day (‘variation margin’); and can be used to cover losses if one of the parties to the derivative defaults (‘initial margin’). [10]

Following IOSCO's initial post-crisis recommendations on securitisation, which were part of the wider shadow banking reform effort, securitisation reform has become a separate workstream under other G20 reform work. For example, work continues on enhancing disclosure and strengthening best practices for investment in structured finance products. [11]

The CFR is the coordinating body of Australia's main financial regulatory agencies (the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), the RBA and the Australian Treasury). For further details on the CFR, see RBA (2018). [12]

As Kearns (2013) notes, APRA had a conservative approach to setting capital rules even before the crisis. For example, 80 per cent of Tier 1 capital had to be of the highest form – ordinary shares and retained earnings – and APRA excluded from Tier 1 items such as intangible assets that had uncertain liquidation values. Rules such as these helped ensure that Australian banks' capital was of a high quality going into the crisis. [13]

The RBA coordinates an annual update to the CFR on developments in, and risks arising from, Australia's shadow banking system, which provides the basis for a CFR discussion. See FSB (2016). [14]

See Medcraft G (2017). [15]

See Orsmond D and F Price (2016). [16]

For a discussion of the concerns regarding CCPs, see Debelle G (2018). On a related point, the financial difficulties at Nasdaq Clearing AB (a Swedish CCP) in September 2018 highlights the types of financial stability issues CCPs can raise. For a discussion of the Nasdaq episode, see RBA (2019), pp 53–54. [17]

See, for example, FSB (2017). [18]

In 2012, the US Financial Stability Oversight Council designated eight ‘financial market utilities’ as systemically important, including several CCPs. [19]

See Quarles R (2019). [20]

References

Debelle G (2018), ‘Lessons and Questions from the GFC’, Address to the Australian Business Economists Annual Dinner, Sydney, 6 December.

FSB (Financial Stability Board) (2016), Thematic Review on the Implementation of the FSB Policy Framework for Shadow Banking Entities, Peer review report, 25 May.

FSB (2017), Guidance on Central Counterparty Resolution and Resolution Planning, 5 July.

FSB (2018), Implementation and Effects of the G20 Financial Regulatory Reforms, 4th Annual Report, 28 November.

Group of Twenty (G20) (2009), G20 Leaders Statement: The Pittsburgh Summit, 24–25 September.

Kearns J (2013), ‘Lessons from the Financial Crisis: An Australian Perspective’, in The Great Recession, J Braude, Z Eckstein, S Fischer and K Flug (eds), The MIT Press, England, pp. 245–268.

Medcraft G (2017), ‘Role of securitisation in funding economic activity and growth’, speech to Global ABS Conference, Barcelona, Spain, 7 June.

Orsmond D and F Price (2016), ‘Macroprudential Policy Frameworks and Tools’, RBA Bulletin, December, pp. 75–86.

Quarles R (2019), ‘Ideas of Order: Charting a Course for the Financial Stability Board’, speech at the Bank for International Settlements Special Governors Meeting, Hong Kong, 10 February.

RBA (Reserve Bank of Australia) (2018), ‘Box E: The Council of Financial Regulators’, Financial Stability Review, October, pp 69–73.

RBA (2019), Financial Stability Review, April.

Schwartz C (2013), ‘G20 Financial Regulatory Reforms and Australia’, RBA Bulletin, September, pp. 77–85.

Yuksel M (2014), ‘Identifying Global Systemically Important Financial Institutions’, RBA Bulletin, December, pp. 63–69.