Reserve Bank of Australia Annual Report – 2021 Operations in Financial Markets

The Reserve Bank operates in domestic and international financial markets to achieve its policy objectives. These operations include implementing the monetary policy decisions of the Reserve Bank Board, facilitating the smooth functioning of the payments system, managing the nation's foreign exchange reserve assets and providing banking services to clients (mainly the Australian Government, as well as foreign central banks).

During 2020/21, the Reserve Bank Board announced further policy measures, building on the comprehensive package of policy measures that had been introduced in early 2020 to support the Australian economy following the outbreak of COVID-19.

In September 2020, an expansion was announced to the Term Funding Facility (TFF), which had been introduced as part of the initial package of policy measures in March 2020. The expansion involved a new ‘supplementary’ funding allowance under the TFF of $57 billion and an extension to the date for last drawdowns to 30 June 2021. The TFF provides funding to banks on a collateralised basis at a low interest rate for a term of three years, with additional funding available to banks that increase their lending to businesses. It is aimed at lowering the cost and supporting the availability of finance, and providing an incentive for banks to increase lending to businesses, particularly small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs).

In November 2020, a further package of policy measures was implemented, comprising:

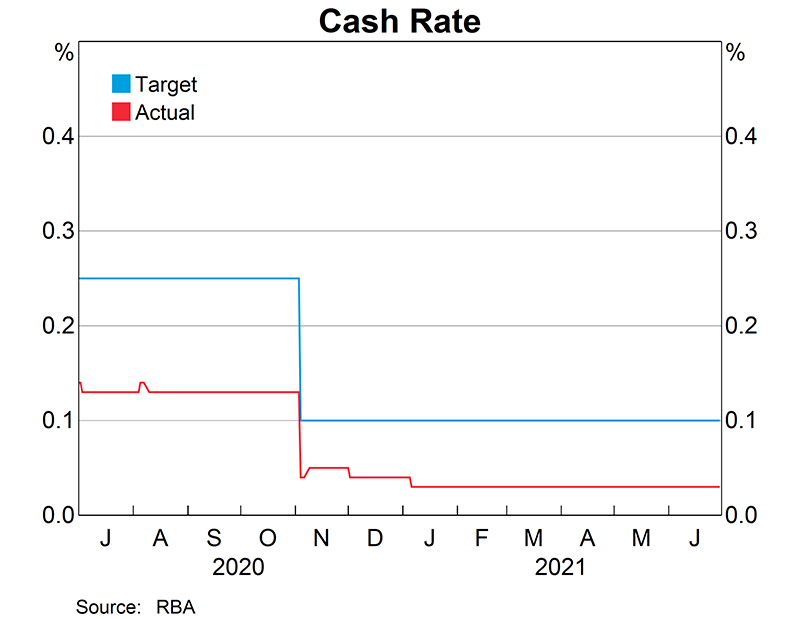

- a reduction in the cash rate target to 0.1 per cent, from 0.25 per cent previously; this followed a cumulative reduction in the cash rate target of 50 basis points in March 2020

- a reduction in the interest paid on Exchange Settlement (ES) balances at the Reserve Bank to zero, from 0.1 per cent previously

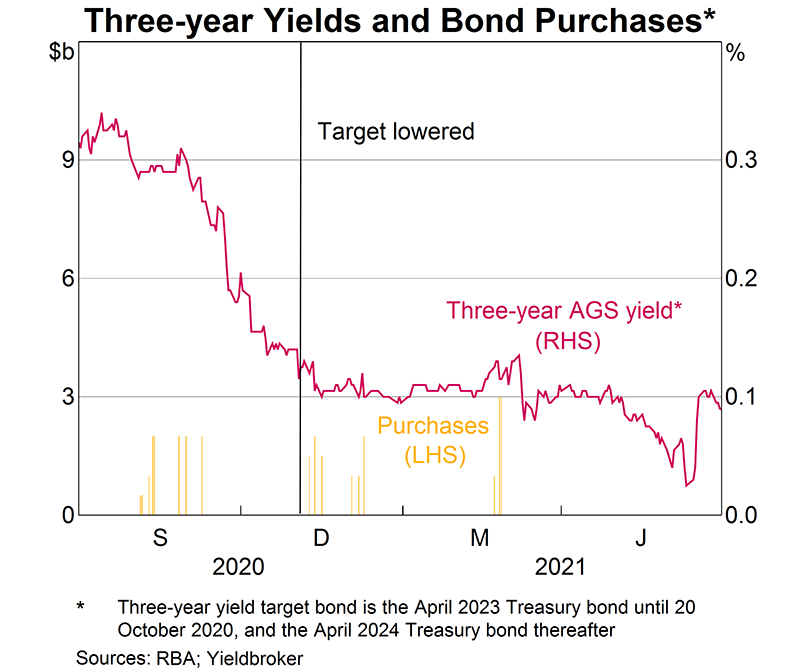

- a reduction in the target for the three-year Australian Government bond yield to around 0.1 per cent, with purchases of government bonds outright in secondary markets to continue to be made as required to help achieve the target; the yield target had previously been 0.25 per cent since its introduction as part of the initial package of policy measures in March 2020. The three-year yield target works to anchor the Australian risk-free yield curve at the target maturity and reinforce the Reserve Bank Board's forward guidance regarding the cash rate

- a reduction in the interest rate on new drawings under the TFF to 0.1 per cent, from 0.25 per cent previously

- the introduction of a government bond purchase program, comprising purchases over six months of $100 billion of longer-dated Australian Government Securities (AGS) and securities issued by the state and territory borrowing authorities (semis), focused on maturities between five and 10 years. This program was aimed at lowering longer-term government bond yields and thereby interest rates more generally (through the risk-free rates embedded in government bond yields), and contributing to a lower exchange rate than otherwise.

Subsequently, in February 2021, the Board announced that a further $100 billion of government bonds would be purchased, following completion of the first $100 billion of purchases, to be completed by September 2021.

The package of policy measures was designed to further lower the structure of interest rates in Australia and thereby support the economy by lowering borrowing costs, continuing to encourage an ample supply of credit to the economy and delivering a lower exchange rate than otherwise.

The policy measures have been working broadly as expected. They have helped to further ease financial market conditions and support the economic recovery following the disruptions associated with the pandemic. The measures have reduced banks' funding costs to historic lows and supported a reduction in housing and business interest rates, which have also reached historic lows.

Monetary policy implementation

Prior to 19 March 2020, the Reserve Bank Board's sole operational target for monetary policy was the cash rate – the rate at which banks borrow and lend to each other on an overnight, unsecured basis. The package of policy measures announced by the Board in response to the economic and financial disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic introduced a number of additional operational targets, as described above. However, the cash rate target remains a key element of the monetary policy framework. The package of policy measures has substantially increased the amount of liquidity in the banking system, with the result that the cash rate has traded below the cash rate target and activity in the cash market has been subdued. This was as expected and is discussed further below.

The funds traded in the cash market are the balances held by financial institutions in their Exchange Settlement Accounts (ESAs) at the Reserve Bank. These accounts are held by around 100 financial institutions and are used to settle payment obligations between these institutions. The aggregate level of ES balances changes as a result of payments made or received by customers of the Bank (principally the Australian Government) and ESA holders, and as a result of transactions undertaken by the Bank on its own behalf. These include undertaking repurchase agreements (repos) collateralised with eligible securities, buying or selling government securities on an outright basis, or using foreign exchange (FX) swaps involving Australian dollars.

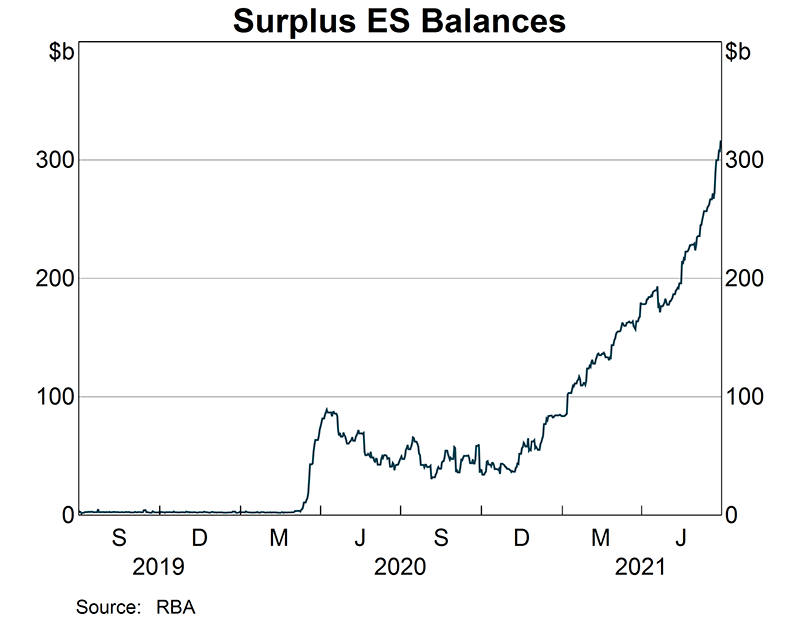

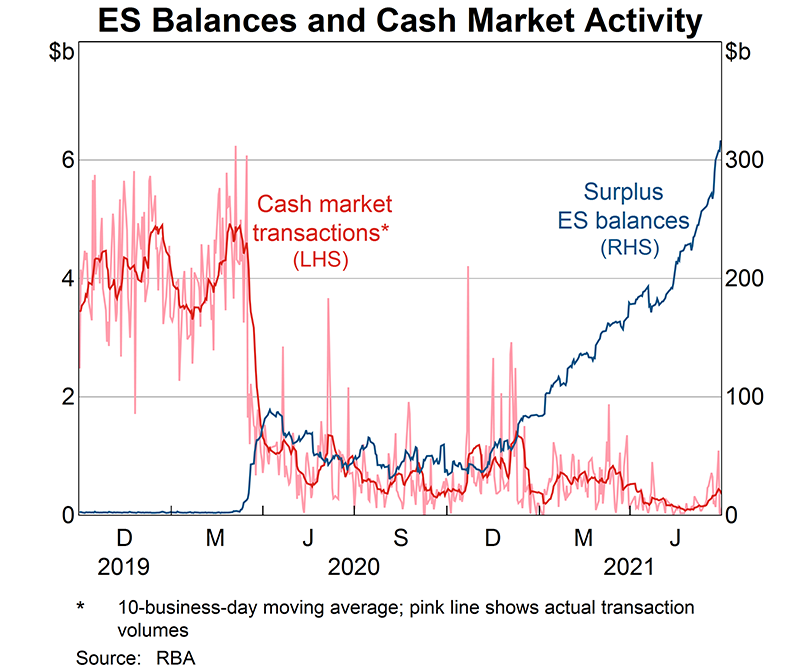

A portion of ES balances arise from ‘open repos’ – these are repos contracted without a maturity date with the Reserve Bank by financial institutions to meet their liquidity needs outside of normal banking hours. These balances are held to facilitate the effective operation of the payments system, and have no implications for the implementation of monetary policy.[1] At the end of June 2021, these balances were $27 billion. The remainder of ES balances, referred to as surplus ES balances, rose from $46 billion at the end of June 2020 to $317 billion at the end of June 2021. This increase was driven by banks' drawings on the TFF (via repos), and by outright government bond purchases by the Reserve Bank under the bond purchase program, discussed further below.

Open market operations

The Reserve Bank undertakes transactions in domestic financial markets to implement the policy decisions of the Reserve Bank Board and facilitate the smooth functioning of the payments system. Historically, this has principally involved the Reserve Bank transacting in domestic financial markets in its open market operations (OMO) to keep the cash rate consistent with the cash rate target set by the Reserve Bank Board. A key class of transaction that the Bank has historically used to achieve this has been repos contracted as part of its regular morning OMO. On occasion, further rounds of market operations were also conducted in the late afternoon if required to ensure the amount of surplus ES balances was consistent with the cash rate trading at target. Repos involve the purchase of high-quality collateral securities where the Bank acquires the securities for a period of time in return for providing cash (i.e. funds deposited into an ESA). As a result, there is very little risk of the Bank suffering financial loss. The securities accepted by the Bank include securities issued by the Australian Government (AGS), the Australian states and territories (semis), and certain approved international sovereign and supranational issuers. Securities issued by banks, asset-backed securities and corporate bonds that meet certain criteria are also eligible for repo in the Reserve Bank's OMO. FX swaps are another type of transaction that the Bank has used to manage system liquidity; swapping Australian dollars for foreign currencies increases the supply of ES balances in the same way as a repo transaction.[2]

In 2020/21, the large increase in surplus ES balances discussed above has meant that the cash rate has traded close to the rate paid on surplus ES balances, rather than at the cash rate target. This was expected and the Reserve Bank has ceased targeting a level of surplus ES balances consistent with the cash rate trading at the target. As a result, FX swaps and afternoon rounds of market operations were not needed for domestic liquidity management purposes in 2020/21. The Reserve Bank has continued to conduct regular morning OMO, but no longer uses these operations to fine-tune financial system liquidity; rather, the Reserve Bank has been providing liquidity through OMO to eligible counterparties at a fixed rate aligned to the cash rate target. Demand for funds at the Bank's regular morning OMO has declined as ES balances have increased, with outstanding OMO repos falling from $97 billon on 30 June 2020 to $7 billion on 30 June 2021. The average term of these transactions was 61 days in 2020/21, down from the average of around 75 days in the early part of the pandemic, but still above the average of around 40 days in the preceding five years.

As noted above, in March 2020 the Reserve Bank Board announced a target for the three-year Australian Government bond yield of around 0.25 per cent, which was subsequently lowered to around 0.10 per cent in November 2020. The three-year target bond was the Australian Government bond with maturity closest to three years. The three-year Australian Government bond yield was consistent with the target over 2020/21. The Bank on occasion purchased three-year government bonds to support the target, but only intermittently. The purchases during 2020/21 totalled $28 billion. The Bank also temporarily increased the fee that it charges counterparties to borrow the three-year target bond, in order to discourage speculation against the target. In particular, the fee was raised from 0.25 per cent to 1 per cent in March 2021 in response to a rise in the three-year Australian Government bond yield away from the target. While there had been a general increase in government bond yields, short-selling of the three-year bond by some market participants who thought the Bank might not maintain the yield target also contributed to the rise in the three-year yield around that time. Governor Lowe reinforced the Board's commitment to the yield target in a speech in March 2021, which also contributed to the subsequent fall in yield.[3] The Bank subsequently reduced the stock-lending fee for the three-year bond back to 0.25 per cent in May 2021.

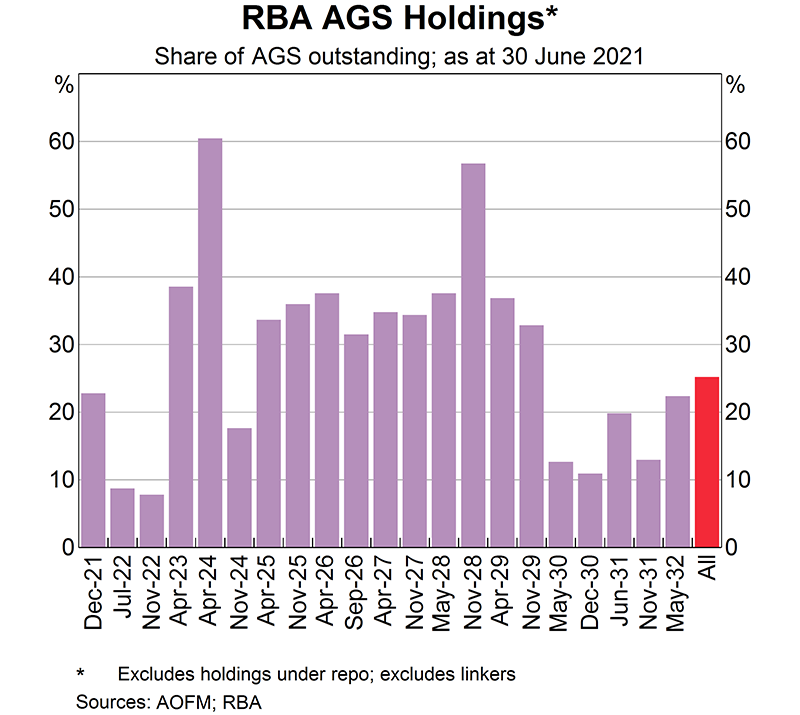

The Reserve Bank commenced purchases under the bond purchase program on 5 November 2020. Purchases were conducted at a pace of $5 billion per week; although public holidays and a break over the 2020/21 Christmas and New Year period resulted in fewer purchases in some weeks. On one occasion in March 2021, the Bank brought forward $2 billion of purchases to assist with bond market functioning, which had become strained following a sharp increase in yields over February 2021. On another occasion in June 2021, an auction was cancelled due to widespread IT issues among the Bank's counterparties in the bond auction. Purchases were conducted via competitive auction, with the Bank purchasing $2 billion of AGS on each of Mondays and Thursdays, and $1 billion of semis on Wednesdays. Purchases were of bonds of around five to 10 years' residual maturity. The Bank purchased a total of $154 billion of government bonds under the bond purchase program during 2020/21, split 80/20 between AGS and semis. The distribution of semis purchased across states and territories was broadly in line with the distribution of debt outstanding.[4]

The Reserve Bank continues to operate a Securities Lending Facility on behalf of the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM). The securities available through the facility comprise all Treasury Bonds and Treasury Indexed Bonds currently on issue. The Bank lends these securities under intraday or open repos to eligible domestic market counterparties. The Bank is also prepared to lend securities from its outright portfolio under repo in response to enquiries from eligible counterparties, and will consider proposals to sell government bonds that it owns outright against an offsetting (duration-neutral) purchase of government bonds; the Bank lent $28 billion of bonds from its outright portfolio over 2020/21, a substantial increase on the $3 billion lent during 2019/20.[5]

Term Funding Facility

Banks had access to three-year funding through the Reserve Bank's TFF throughout 2020/21. The facility closed to new drawdowns on 30 June 2021, but will continue to provide low-cost funding to banks for up to three years ending June 2024.

As outlined above, during 2020/21 the Board enhanced the support available to banks through the TFF from October 2020 by introducing a ‘supplementary’ funding allowance, fixed at 2 per cent of a bank's overall credit and extending the date for last drawdowns to 30 June 2021. In November 2020, the rate on TFF drawings was reduced to 0.10 per cent, in line with the reduction in the cash-rate target at that time.

In combination with the Bank's other policy measures, the TFF contributed to lower funding costs for banks and lower lending rates. The price of the TFF was well below banks' marginal cost of funding around that same maturity throughout 2020/21. For example, the estimated cost of sourcing three-year unsecured funding in domestic wholesale debt markets for the major banks was around 0.6 per cent at the end of June 2021, and somewhat higher for the other banks.

In addition to reducing banks' funding costs, the TFF encouraged banks to support businesses during a difficult period by providing a bank access to additional low-cost funding if it expanded its lending to businesses, particularly to SMEs. In addition to a bank's ‘initial’ allowance under the TFF (set at 3 per cent of a bank's overall credit), a bank's ‘additional’ allowance increased by $1 for every extra dollar it lent to large businesses and by $5 for every extra dollar it lent to SMEs. The bulk of additional allowances available in June 2021 were due to increases in SME lending by some banks.

Given the growth in the additional allowances for a range of banks, the total funding available under the TFF to banks was $213 billion, comprised of: initial allowances (which closed in September 2020) totalling $84 billion; supplementary allowances totalling $57 billion; and additional allowances totalling $72 billion.

By the close of the TFF drawdown period on 30 June 2021, 92 banks – around two-thirds of those eligible – had accessed $188 billion of funding through the TFF, representing total take up of 88 per cent of the value available.[6] Drawdowns from the TFF were concentrated close to the end of the drawdown periods, reflecting banks' strong funding positions prior to the pandemic and the large amount of liquidity available through other sources.

Balance sheet

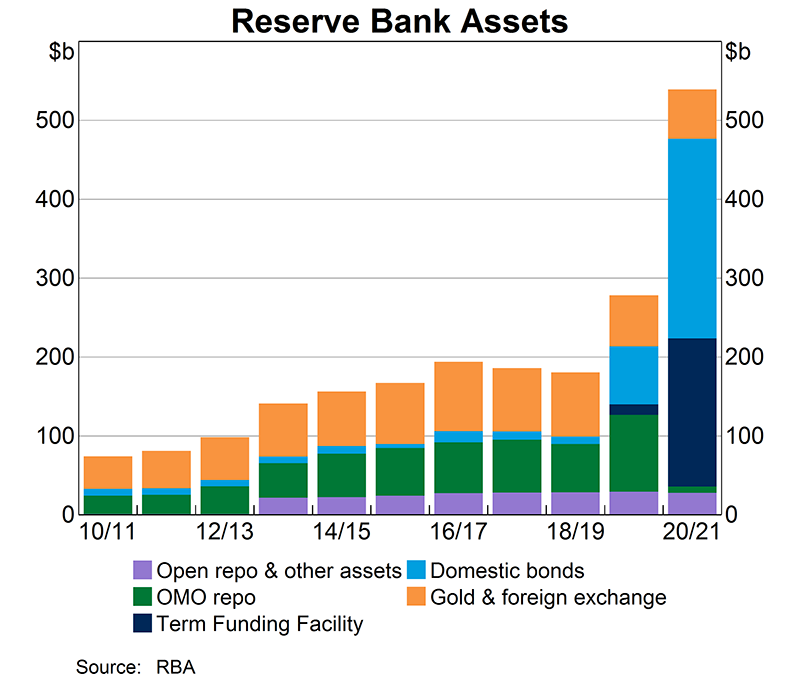

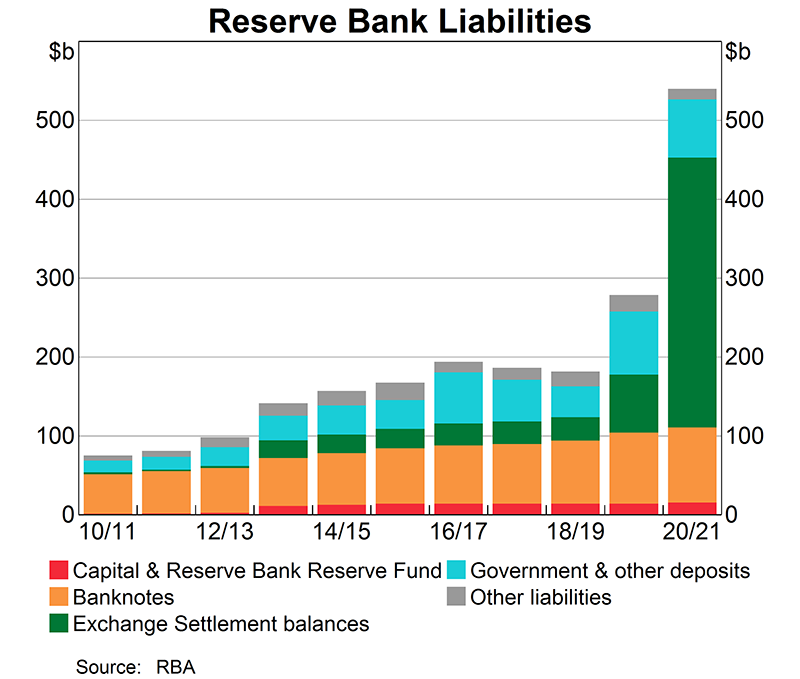

The Reserve Bank's balance sheet has almost tripled in size since the onset of COVID-19 as a result of the policy measures adopted by the Bank to support the Australian economy. Over the 2020/21 financial year, the balance sheet increased by $279 billion to $540 billion. Growth in assets reflected an increase in the Bank's government bond holdings, purchased in support of the three-year yield target and under the bond purchase program, and an increase in the TFF. This was partly offset by a decline in funds lent via OMO, as discussed above. The corresponding growth in liabilities was primarily due to a large increase in ES balances, which resulted from the Reserve Bank's policy measures. Government deposits remained at a high level by historical standards.

| 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|

| Assets | 279 | 540 |

| Foreign | 65 | 63 |

| Domestic | 214 | 477 |

| Outright bond holdings | 73 | 253 |

| OMO repo | 97 | 7 |

| Term Funding Facility | 14 | 188 |

| Open repo & others | 30 | 29 |

| Liabilities | 279 | 540 |

| Deposits | 154 | 416 |

| ES balances | 73 | 342 |

| Government & other | 80 | 74 |

| Banknotes | 90 | 95 |

| Other | 21 | 15 |

| Capital and Reserve Bank Reserve Fund | 14 | 14 |

|

Source: RBA |

||

Standing facilities

Separate from its OMO, the Reserve Bank also provides certain standing facilities, where eligible counterparties transact with the Bank on pre-arranged terms. These facilities are primarily to support the smooth functioning of the payments system, with liquidity made available via repos. The most frequently used standing facilities are those for the provision of intraday liquidity to ESA holders. The Bank can also extend overnight funding via repo where an ESA holder faces a shortage in ES balances that cannot be borrowed from another financial institution; such funding is extended at an interest rate of 25 basis points above the cash rate target. During 2020/21, these arrangements were used on two occasions, one of which was for testing purposes.

Open repos are provided under the Reserve Bank's standing facilities for ESA holders, and in 2020/21 remained mandatory for ESA holders that have to settle payment obligations outside normal business hours, such as ‘direct-entry’ payments and transactions through the New Payments Platform (see chapter on ‘Banking and Payment Services’). At the end of June 2021, 15 financial institutions had open repo positions with the Bank, valued at around $27 billion. To collateralise these open repos, the Bank permits the use of certain related-party assets issued by bankruptcy remote vehicles, such as self-securitised residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS).

Committed Liquidity Facility

Banks subject to the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) under Basel III prudential standards are required to hold sufficient high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) (which, in the Australian context, consist of AGS, semis and ES balances) to meet outflows during a period of stress of 30 days. Historically, the relatively low levels of government debt outstanding in Australia have limited the amount of HQLA securities that banks could reasonably hold. To address this, since 2015 the Reserve Bank has provided some institutions with a contractual commitment to provide repo funding – the Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF) – subject to certain conditions. These conditions include a fee that financial institutions pay on the committed amount. In addition, any bank seeking to use the CLF must have positive net worth. The full terms and conditions of the facility are available on the Bank's website.[7]

The Reserve Bank administers the CLF, while the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) determines which banks have access and the amount available (in aggregate and to each bank). Fifteen banks had access to the CLF from July 2020 to December 2020; 14 banks had access to the CLF from January 2021 to June 2021. The available CLF amounts for each of these banks is counted towards their LCR requirements. The aggregate size of the CLF is the difference between APRA's assessment of banks' overall LCR requirements and the Bank's assessment of the amount of HQLA securities that could reasonably be held by the banking system, without unduly affecting market functioning. APRA also incorporates its projections of banks' holdings of banknotes and ES balances.

In determining the amount of HQLA securities that LCR banks can reasonably be expected to hold, the Reserve Bank takes into account factors such as the total stock of HQLA securities, holdings of other market participants and the effect of LCR banks' holdings on the liquidity of HQLA securities in secondary markets. Over recent years, the stock of HQLA securities has risen and they have become more readily available in bond and repo markets. In 2020, the stock of AGS and semis outstanding increased substantially as the federal, state and territory governments issued bonds to finance the fiscal response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Given this, the Reserve Bank assessed that the LCR banks could increase their holdings of AGS and semis from 26 per cent to 27 per cent of the stock outstanding by the end of 2020 and to 30 per cent of the stock in 2021.

Reflecting the increased availability of HQLA, as well as improvements in funding and liquidity conditions for banks, the total size of the CLF had declined to $139 billion by June 2021, down from $226 billion in July 2020.[8]

The CLF fee is set so that the banks face similar financial incentives to meet their liquidity requirements through the CLF or by holding HQLA. From 2015 to 2019, the Reserve Bank charged a fee of 15 basis points per annum on the commitment to each bank. Following a review in 2019, the CLF fee has been increased gradually, to 17 basis points on 1 January 2020 and to 20 basis points on 1 January 2021.[9]

Eligible securities

The Bank accepts a range of eligible Australian dollar collateral for its daily market operations, including:

- securities issued by the Australian Government and the states and territories

- securities issued by authorised deposit-taking institutions and non-bank corporations with an investment-grade credit rating

- asset-backed and other securities with an average credit rating of AAA (for long-term securities) and A-1 (for short-term paper).[10]

To protect against a decline in the value of the collateral securities should the Bank's counterparty not meet its repurchase obligations, the Bank requires the value of the securities to exceed the cash lent by a specific margin. These margins, which are listed on the Bank's website, are considerably higher for securities that are not issued by governments.[11]

Participants in the Reserve Bank's market operations tend to be the fixed-income trading desks of banks and securities firms, as well as bank treasuries. Reflecting this, over half of the securities held by the Bank (excluding those under open repo and the TFF) are government-related obligations.

Domestic securities purchased by the Reserve Bank are held in an account that the Bank maintains in Austraclear – the central securities depository operated by the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX). Securities transactions conducted between the Bank and its counterparties are settled in the Austraclear system, mostly on a bilateral basis. The Bank also settles repo transactions contracted in its OMO within ASX Collateral, a collateral management service. During 2020/21, almost 50 per cent of the value of securities the Bank purchased under repo in OMO was settled within ASX Collateral, up from around 40 per cent in 2019/20. The use of this system reduces the manual processing that would otherwise be required to manage this collateral, including marking it to market and maintaining margins.

Asset-backed securities form a significant share of the securities that the Reserve Bank purchases under open repo and under the TFF. Around 90 per cent of the outstanding value of open repos is backed by self-securitised RMBS; the figure is similar for the TFF. (Self-securitised RMBS are not eligible as collateral for daily OMO repos.) Self-securitised RMBS do not have directly observable market prices. As a result, the Bank uses an internal valuation model for self-securitised RMBS based on observed market prices of similarly structured RMBS; this internal model has been reviewed externally.

Asset-backed securities – particularly self-securitised RMBS – are also the major asset held as collateral by banks for the CLF (see above). Given the importance of asset-backed securities to the Reserve Bank's operations, the Bank has mandatory reporting requirements for securitisations to remain eligible for repo. In 2020/21, the Bank received around 4,500 data submissions monthly on around 350 asset-backed securities from issuers or their appointed information providers. For eligible RMBS, this covers around 2 million underlying individual housing loans with a combined balance of around $620 billion, which is around one-third of the total value of housing loans in Australia. The required data include key information on the structure of the RMBS, the relationships among counterparties within the RMBS structure, and anonymised information on each of the residential mortgage loans and the underlying collateral backing the RMBS structures.

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $ billion | per cent of total |

$ billion | per cent of total |

$ billion | per cent of total |

$ billion | per cent of total |

|

| AGS | 49.9 | 48 | 36.5 | 37 | 47.4 | 31 | 5.6 | 2 |

| Semis | 8.7 | 8 | 12.7 | 13 | 25.2 | 16 | 8.1 | 3 |

| Supranational | 3.6 | 3 | 2.8 | 3 | 3.4 | 2 | 0.7 | 0 |

| ADI issued | 8.1 | 8 | 12.9 | 13 | 27.8 | 18 | 11.2 | 4 |

| Corporate issued | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 |

| Asset-backed securities | 32.7 | 32 | 33.5 | 34 | 50.0 | 32 | 260.2 | 91 |

| – of which for open repo |

32.3 | 31 | 32.4 | 33 | 32.4 | 21 | 31.5 | 11 |

| – of which for TFF |

0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 14.7 | 9 | 227.8 | 80 |

| – of which for OMO | 0.4 | 1 | 1.1 | 1 | 2.9 | 2 | 0.9 | 0 |

| Other | 0.6 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 1.1 | 1 | 0.2 | 0 |

| Total | 103.7 | 100 | 98.8 | 100 | 155.2 | 100 | 286.3 | 100 |

| – of which for open repo | 34.2 | 33 | 34.5 | 35 | 35.3 | 23 | 34.3 | 12 |

| – of which for TFF | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 17.7 | 11 | 244.6 | 85 |

| – of which for OMO | 69.5 | 67 | 64.3 | 65 | 102.2 | 66 | 7.4 | 3 |

|

(a) Market value of securities before the application of margins; includes securities held under triparty repurchase agreements Source: RBA |

||||||||

Reflecting the Reserve Bank's interest in promoting transparency for investors in asset-backed securities, issuers are also required to make securitisation information available to investors and other permitted users. The data provided to these users are broadly similar to the data provided to the Bank; however, issuers may redact particular fields where the information poses a potential risk to privacy obligations and provide aggregated data instead. The mandatory reporting requirements allow the Bank (and other investors in RMBS) to analyse in detail the underlying risks in asset-backed securities and to price and manage risk for such securities accurately.

The cash rate

The Reserve Bank is the administrator of the cash rate, which is a significant financial benchmark referenced in overnight indexed swaps and the ASX's 30-day interbank cash rate futures contracts, as well as in securities and transactions requiring a (near) risk-free reference rate (RFR). The cash rate is also known as AONIA (AUD Overnight Index Average). As the RFR for the Australian dollar, it forms the basis of the fallback to the bank bill swap rate (calculated as AONIA plus a spread) under International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) definitions published in 2020.[12] These definitions were developed in the context of global benchmark reforms, which have included identifying alternatives to credit-based rates for use in securities and transactions.[13] The Bank publishes the Cash Rate Procedures Manual, which sets out the Bank's arrangements for administering the cash rate and the procedures for handling errors and complaints.[14]

Activity in the cash market fell over 2020/21 as ES balances increased, and on around 60 per cent of days activity was below the thresholds required to calculate a reliable cash rate based on market transactions. In accordance with the published fallback procedures, the published cash rate on these days was the last cash rate published based on sufficient transactions (148 occasions), or another rate that reflected the interest rate relevant to unsecured overnight funds for cash market participants as determined by the cash rate administrator, in its expert judgement and based on market conditions (two occasions).

The cash rate was below the cash rate target over 2020/21, at around 13 to 14 basis points until November 2020 compared with a target of 25 basis points, and then around 3 basis points following a reduction in the cash rate target to 10 basis points at the November Reserve Bank Board meeting.[15] The cash rate trading below the target, and close to the ES remuneration rate, was an expected consequence of elevated ES balances. This is consistent with the experience of other central banks that have pursued programs that significantly increased cash reserves in the banking system.

Foreign exchange operations

The Reserve Bank transacts in the FX market on almost every business day. The majority of these transactions are associated with providing foreign exchange services to the Bank's clients, the most significant of which is the Australian Government.

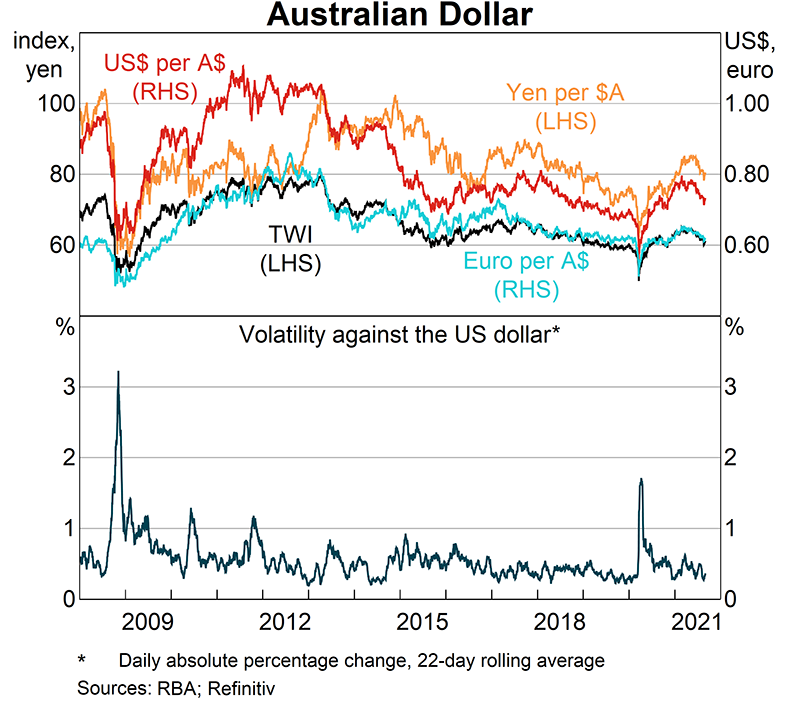

The Reserve Bank typically purchases the necessary foreign currency in the spot market. During 2020/21, the Bank bought $13 billion in the spot market to facilitate its customer business. However, the Bank retains the option – especially during periods of market stress – to use its existing stock of foreign currency reserves to fund its customer business, subsequently replenishing those reserves when market conditions have stabilised. Using foreign currency reserves in this manner has not been considered necessary since 2008, at which time global financial market functioning was significantly impaired. Similarly, the Bank has not intervened in the FX market since 2008. During 2020/21, the Bank's assessment was that trading conditions in the market were sufficiently orderly that it was not necessary to support liquidity in the market through its own transactions. The Bank nevertheless retains the discretion to intervene in the FX market to address any dysfunction and/or a significant misalignment in the value of the Australian dollar. At the time each Annual Report is published, intervention data for the year under review are published on the Bank's website.[16]

The Reserve Bank also transacts in the FX market when managing its foreign currency reserves. As discussed below, the relative weightings of foreign currencies in the Bank's portfolio are tightly managed against a benchmark. To maintain the portfolio at these benchmark weights, or to accommodate discrete changes in the weights, the Bank transacts in spot FX markets. The final settlement of these rebalancing flows may be deferred for a short period of time through the use of FX swaps, whereby one currency is exchanged for another with a commitment to unwind the exchange at a subsequent date at an agreed (forward) rate. Swaps can also be an efficient way to manage the shorter-term investments within the reserves portfolio. During 2020/21, the Bank generally maintained around $18 billion in swaps for these purposes.

For many years, the Reserve Bank has also made use of short-term FX swaps in its domestic market operations. These swaps between Australian dollars and foreign currencies do not affect the exchange rate, but alter the supply of ES balances in the same way as the Bank's repo transactions. The change in the nature of the Bank's domestic market operations after March 2020 means that the Bank did not use swaps for this purpose during 2020/21.

The Bank also executes long-term FX swaps against Australian dollars for terms of up to five years. As discussed below, these longer-term transactions are used to obtain foreign currency to meet Australia's commitments as a member of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (e.g. providing foreign currency to the IMF to support its lending activities).[17] As with short-term swaps, these long-term swaps do not affect the exchange rate. The Bank had US$3.4 billion in long-term swaps outstanding at the end of June 2021.

The Bank's forward foreign exchange positions with each of its counterparties are marked to market daily and collateral is held against net exposures. The terms under which collateral is exchanged are defined in two-way credit support annexes to the ISDA Master Agreements that the Bank has executed with each of its counterparties (see chapter on ‘Risk Management’).

The Reserve Bank's activities in the FX market are conducted in a manner consistent with the principles of the FX Global Code. A ‘Statement of Commitment to the FX Global Code’ has been signed on behalf of the Bank.[18] Further, the Bank transacts in the FX market only with counterparties that have also signalled their adherence to the Code by signing such statements.

Reserves management

Australia's official reserve assets include foreign currency assets, gold, Special Drawing Rights (SDRs, an international reserve asset created by the IMF) and Australia's reserve position in the IMF. At 30 June 2021, these assets totalled $64.7 billion, with all components of official reserve assets owned and managed by the Reserve Bank, with the exception of Australia's reserve position in the IMF, which is an asset of the Australian Government.

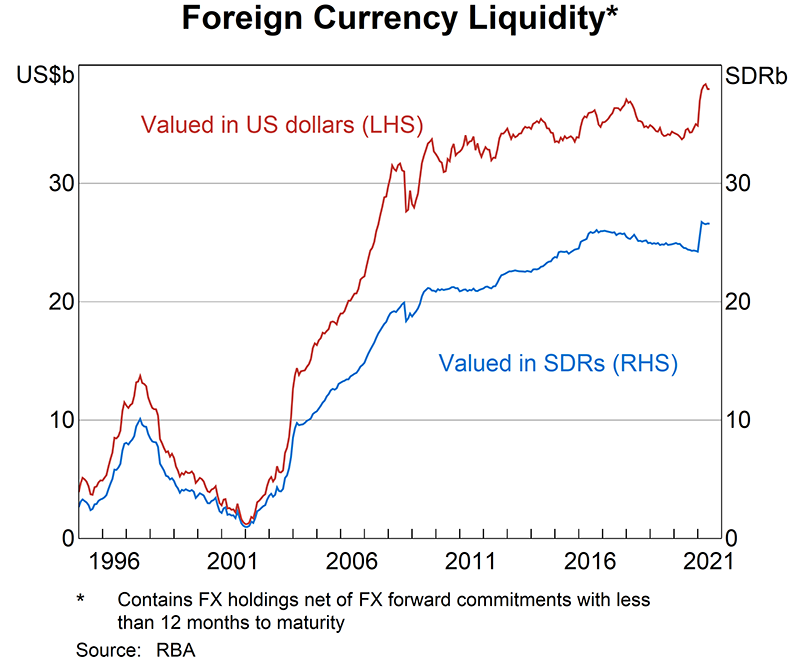

Official reserve assets are held by the Reserve Bank to facilitate various policy operations, including in the FX market (described above) and to assist the Australian Government in meeting its commitments to the IMF. The Bank's capacity to undertake such operations is best measured by its foreign currency assets net of any short-term forward commitments (such as an obligation to deliver foreign currency on the maturity of a swap against Australian dollars). As at 30 June 2021, these assets – referred to by the IMF as ‘foreign currency liquidity’ – were SDR26.6 billion or US$38.0 billion. In US dollar terms, foreign currency liquidity increased by US$4.1 billion from 30 June 2020, reflecting purchases of foreign currency under long-term swaps and gains from appreciation of other reserve currencies against the US dollar. The amount held represents the level assessed as necessary to meet policy requirements.

To ensure a strong balance sheet, the Reserve Bank holds capital against certain risks arising from its reserve assets (see chapter on ‘Earnings, Distribution and Capital’). These assets can expose the Bank to market, liquidity and credit risk, which the Bank seeks to mitigate where possible, such as by holding a diversified portfolio and investing only in assets of high credit quality and appropriate liquidity (see chapter on ‘Risk Management’).

| A$ million | |

|---|---|

| Official reserve assets | |

| Foreign currency | 50,284 |

| Gold | 5,568 |

| SDRs | 5,459 |

| Reserve position in the IMF | 3,423 |

| Other foreign currency assets | 18 |

| Net forward foreign currency commitments: Short-term | |

| Foreign currency | 206 |

| Gold loans and swaps | 453 |

| Net forward foreign currency commitments: Long-term | −4,374 |

| Memo item: | |

| Foreign Currency Liquidity (FX)(a) | 50,508 |

|

(a) Foreign currency liquidity (FX) includes foreign currency holdings and other foreign currency assets, net of short-term foreign currency forward commitments (commitments with less than 12 months to maturity) Source: RBA |

|

Net of forward commitments against the Australian dollar, the composition of the Reserve Bank's foreign currency reserve holdings is managed against an internally constructed benchmark that reflects the Bank's need to maintain effective intervention capacity. Subject to this constraint, and the Bank's overall risk tolerance, the benchmark is assessed to be the combination of foreign currencies and foreign currency assets that maximises the Bank's expected returns over the long run.

The structure of the benchmark is reviewed periodically and in response to significant changes in market conditions. The existing structure of the benchmark portfolio has been assessed as remaining suitable for the Reserve Bank's needs. Within the portfolio, the largest allocation is to the US dollar (55 per cent), reflecting the significant liquidity in US dollar currency and asset markets.

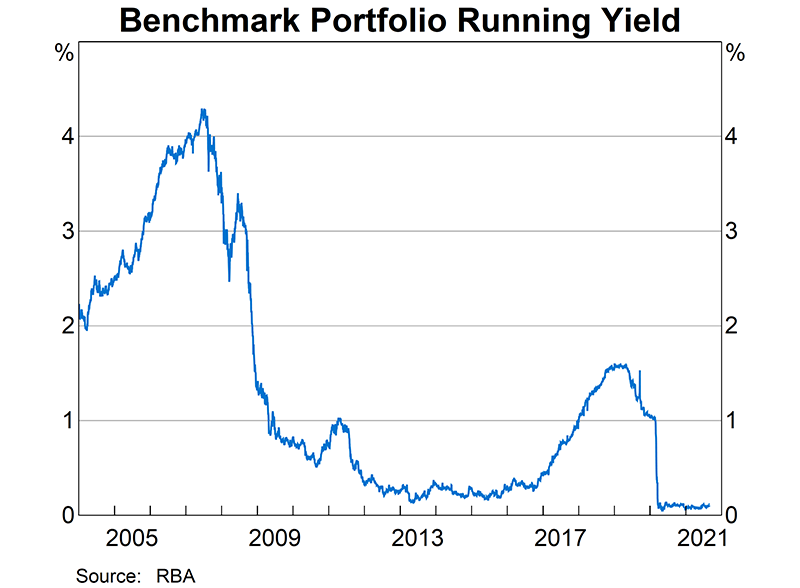

Given the extraordinarily low level of global interest rates, duration targets have remained short for most of the foreign currency portfolios because this reduces the risk of capital losses in the event yields in these currencies increase in the future.

Investments in the benchmark currencies are limited to deposits at official institutions (such as central banks) and debt instruments issued (or guaranteed) by sovereign entities, central banks and supranational agencies. Debt instruments issued by quasi-sovereign entities can also be accepted as collateral under reverse repos.

Sovereign credit exposures are currently limited to the United States, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Canada, Japan, China, the United Kingdom and South Korea.

| US dollar | Euro | Japanese yen | Canadian dollar | Chinese renminbi | UK pound sterling | South Korean won | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Currency allocation (per cent of total) |

55 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Duration (months) | 6 | 6 | <3 | 6 | 18 | 3 | 18 |

|

Source: RBA |

|||||||

As has been the case for some years, when the cost of hedging currency risk is taken into account, yields on short-dated Japanese and South Korean investments have generally exceeded those available in the other currencies in the Reserve Bank's portfolio. Reflecting this, the Bank has swapped other currencies in its foreign exchange reserves portfolio against the Japanese yen and South Korean won to enhance returns. As a consequence, while the Bank's exposure to changes in the value of the yen and won remains small (the allocation to each of these currencies was $2.2 billion), an additional $21.8 billion of yen and $2.2 billion of won was held at the end of June 2021 as a result of swaps against other foreign currencies in the portfolio.

A small component of the Reserve Bank's foreign currency risk is managed outside the benchmark framework. The Bank invests in a number of Asian debt markets through participation in the Executives' Meeting of East Asia-Pacific Central Banks (EMEAP) Asian Bond Fund Initiative. This initiative was established following the Asian currency crisis in the late 1990s to assist in the development of bond markets in the region. At the end of June 2021, the total allocation of the Bank's reserves to these funds was $720 million. In SDR terms, there was a return of 0.4 per cent on these investments over the year to June 2021, as gains from Asian currency appreciation were partly offset by capital losses on Asian government bonds as yields rose.

Measured in SDRs, the overall return on the Reserve Bank's foreign currency assets over 2020/21 was −0.7 per cent. This was lower than returns observed in recent years, reflecting exchange rate movements and capital losses as yields rose on longer-term securities. The average running yield on the benchmark portfolio remained at 0.1 per cent over 2020/21. Yields remained negative and relatively stable for the euro portfolio.

The Reserve Bank's holdings of SDRs at 30 June 2021 amounted to $5.5 billion – $0.9 billion lower than the previous year – reflecting provision of SDRs to the IMF's Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust, as well as appreciation of the Australian dollar against the SDR. Under voluntary arrangements with the IMF, the Bank is willing to transact in SDRs upon request from other countries or prescribed holders. In these transactions, the Bank will generally either buy or sell SDRs in exchange for foreign currencies (such as euros or US dollars). While such transactions do not alter the level of Australia's reserve assets (only the respective proportions held in SDRs and foreign currency), the Bank will typically replenish foreign currency sold in exchange for SDRs by purchasing foreign currency in long-term swaps against Australian dollars.

Australia's reserve position in the IMF comprises that part of Australia's quota in the IMF that is paid in foreign currency as well as other credit that Australia has extended to the IMF in support of its lending programs. At the end of June 2021, Australia's reserve position in the IMF was $3.4 billion – $0.3 billion larger than a year earlier – because the provision of more foreign currency to the IMF was partly offset by valuation effects from an appreciation of the Australian dollar. As noted above, Australia's reserve position in the IMF is not held on the Bank's balance sheet. However, the Bank will sell to (or purchase from) the Australian Treasury the foreign currency the Treasury needs to complete its transactions with the IMF. As with SDR transactions, the Bank will typically replenish the foreign currency sold to the Treasury by purchasing foreign currency in long-term swaps against Australian dollars.

| Currency | Securities held outright | Securities lent under repurchase agreements | Deposits at official institutions(b) | Total (gross) | Forward FX commitment(c) | Total (net) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Against A$ | Against other currencies | Other | ||||||

| US dollar | 10,629 | - | 736 | 11,364 | −4,602 | 18,000 | 281 | 25,043 |

| Euro | 2,912 | - | 1,171 | 4,083 | −13 | 4,895 | - | 8,965 |

| Japanese yen | 11,110 | - | 12,811 | 23,921 | - | −21,762 | - | 2,159 |

| Canadian dollar | 1,142 | - | 4 | 1,146 | - | 1,208 | - | 2,354 |

| Chinese renminbi | 1,810 | - | 540 | 2,350 | - | - | - | 2,350 |

| UK pound sterling | 2,347 | - | 11 | 2,358 | −7 | 1 | - | 2,352 |

| South Korean won | 4,387 | - | 6 | 4,392 | - | −2,194 | - | 2,198 |

| Total | 34,336 | - | 15,278 | 49,615 | −4,622 | 147 | 281 | 45,421 |

|

(a) Excludes gold, SDRs, the reserve position in the IMF, investments in the Asian

Bond Fund, balances with overseas banks, futures margins and non-reserve currency

holdings Source: RBA |

||||||||

Gold holdings (including gold on loan) at the end of June 2021 were around 80 tonnes, unchanged since 1997. Gold prices declined by 8.6 per cent in Australian dollar terms over 2020/21, decreasing the value of the Reserve Bank's holdings of gold by around A$0.6 billion to A$6.1 billion. The Bank also seeks to earn income on its holdings by lending gold. Any gold lending by the Reserve Bank has the benefit of a government guarantee on the borrower's payment obligations to the Bank or is structured as a gold swap, such that the loan is fully collateralised by cash (either foreign currency or Australian dollars). Returns from these activities totalled $1.3 million in 2020/21, slightly lower than the previous financial year. The lower returns were due to both a small decline in lending rates and decreased activity. As at 30 June 2021, the Reserve Bank had outstanding gold loans amounting to 6 tonnes, a decrease from 24 tonnes at the end of the previous financial year (of which 11 tonnes had been delivered into swaps). Gold that has not been lent is held by the Reserve Bank in an allocated account at the Bank of England and comprises bars that meet the London Bullion Market Association's ‘Good Delivery’ standards. The Bank's activities in the gold market are conducted in a manner consistent with the principles of the Global Precious Metals Code, and a ‘Statement of Commitment to the Global Precious Metals Code’ has been signed on behalf of the Bank.[19]

Bilateral currency swaps

In July 2021, the Reserve Bank renewed its bilateral local currency swap agreement with the People's Bank of China. The agreement allows for the exchange of local currencies between the two central banks of up to A$41 billion or CNY 200 billion. This agreement is for a further five years and can be extended by mutual consent. The Reserve Bank has similar agreements with the Bank of Japan, Bank of Korea and Bank Indonesia. The purpose of these agreements is to allow each central bank to support trade settlement in local currencies, particularly in times of market stress, or to support financial stability.

The Reserve Bank has a temporary swap line with the US Federal Reserve, which was established in March 2020 when the COVID-19 outbreak led to US dollar funding pressures within global financial markets.[20] The Federal Reserve established temporary arrangements with eight other central banks at the same time, in addition to the standing US dollar swap lines it maintains with five major central banks. The Reserve Bank's US$60 billion swap line allows it to exchange Australian dollars for US dollars. The US dollars can be made available to Australian market participants through repos against Australian dollar-denominated securities. There was no usage of this swap line during 2020/21. The agreement with the Federal Reserve is due to expire in December 2021.

| Expiry | Size (A$ billion) | |

|---|---|---|

| People's Bank of China | July 2026 | 41 |

| Bank of Japan | March 2022 | 20 |

| Bank Korea | February 2023 | 12 |

| Bank of Indonesia | December 2021 | 10 |

| Federal Reserve | December 2021 | 80 |

|

Source: RBA |

||

Endnotes

Given institutions are required to contract open repos to support the smooth functioning of the payments system, pricing is set so that there is no net interest cost to holding an open repo position. From November 2020, open repos have been priced at, and the associated funds remunerated at, the interest rate paid on surplus ES balances. Prior to this, since the introduction of open repos in 2013, the relevant price/remuneration rate had been the cash rate target. This change was made for technical reasons, with the principle of remunerating open repos and the resulting ES balances at the same rate unchanged. [1]

While the use of FX swaps can increase the Reserve Bank's holdings of foreign exchange, it has no effect on net foreign reserves, as the increased holdings of foreign exchange are matched with a commitment to sell foreign exchange at a predetermined price and date. For the same reason, the use of swaps has no effect on the exchange rate. [2]

See Lowe P (2021), ‘The Recovery, Investment and Monetary Policy’, Speech at AFR Business Summit, 10 March. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2021/sp-gov-2021-03-10.html> [3]

For details of bonds purchased under the program, see RBA (2021), ‘Statistical Table A3’. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/tables>. [4]

For details of the Reserve Bank's securities lending repurchase transactions and switch transactions, see RBA (2021), ‘Statistical Table A3.2’. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/tables>. [5]

See RBA (2021), ‘Box C’, Statement on Monetary Policy, August. [6]

See RBA (2019), ‘Committed Liquidity Facility – Terms and Conditions’. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/mkt-operations/resources/tech-notes/pdf/clf-terms-and-conditions.pdf>; RBA (2019), ‘CLF Operational Notes’. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/mkt-operations/resources/tech-notes/clf-operational-notes.html>. [7]

See RBA, ‘Committed Liquidity Facility’. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/mkt-operations/committed-liquidity-facility.html>; Brischetto A and L Jurkovic (2021), ‘The Committed Liquidity Facility’, RBA Bulletin, June. APRA had also allowed banks to use undrawn allowances for the Reserve Bank's TFF towards meeting their LCR while these allowances were still available to be drawn. The drawdown window for the TFF closed on 30 June 2021. [8]

For an explanation of the adjustments made to the CLF, see Kent C (2019), ‘The Committed Liquidity Facility’, Speech at Bloomberg, Sydney, 23 July. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2019/sp-ag-2019-07-23.html>; Bergmann M, E Connolly and J Muscatello (2019), ‘The Committed Liquidity Facility’, RBA Bulletin, September. [9]

The Bank broadened the range of eligible collateral for its daily market operations to include Australian dollar securities issued by non-bank corporations with an investment grade credit rating in May 2020. See RBA (2020), ‘Eligible Securities’. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/mkt-operations/resources/tech-notes/eligible-securities.html>. A total of 187 such securities have been approved as eligible, but their use as collateral is limited. [10]

See RBA (2020), ‘Margin Ratios’. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/mkt-operations/resources/tech-notes/margin-ratios.html>. [11]

See ISDA (2020), ‘Amendments to the 2006 ISDA Definitions to Include New IBOR Fallbacks’, 23 October. Available at <http://assets.isda.org/media/3062e7b4/23aa1658-pdf></sup>. [12]

See chapter on ‘International Financial Cooperation’ for details of the Financial Stability Board's work on reforming interest rate benchmarks globally. [13]

See RBA (2020), ‘Cash Rate Procedures Manual’. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/mkt-operations/resources/cash-rate-methodology/cash-rate-procedures-manual.html>. [14]

For many years in Australia there had been a market convention for overnight cash market transactions to be conducted at the target cash rate. However, given the very high level of ES balances, with most banks' balances well above holdings sufficient for usual payment activities, this convention changed and market participants instead began to trade below the cash rate target when lending cash overnight. [15]

See RBA (2021), ‘Statistical Table A5’. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/tables>. [16]

See Kent C (2021), ‘FX Markets Around the Turn of the Year’, Speech at Australian Corporate Treasury Association FX Roundtable, Webinar, 17 February. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2021/sp-ag-2021-02-17.html>. [17]

See RBA (2017), ‘Statement of Commitment to the FX Global Code’, 7 November. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/mkt-operations/pdf/statement-of-commitment-to-fx-global-code.pdf>. [18]

See RBA (2019), ‘Statement of Commitment to the Global Precious Metals Code’, 27 September. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/mkt-operations/pdf/statement-of-commitment-to-the-global-precious-metals-code-february-2019.pdf>. [19]

A prior swap agreement with the Federal Reserve expired in 2010. [20]