Bulletin – September 2019 Payments A Brief History of Currency Counterfeiting

- Download 674KB

Abstract

The crime of counterfeiting is as old as money itself, and can be targeted at both low- and high-value denominations. In most cases, counterfeiting is motivated by personal gain but, at times, it has also been used as a political weapon to destabilise rival countries. This article gives a brief history of counterfeiting, with a particular focus on Australia, highlighting selected incidents through time and the policy responses to them. For source material on Australia, we draw on Reserve Bank archives dating back to the early 1900s.

Introduction

Historical evidence suggests that, for as long as physical money has existed, it has been counterfeited.[1] The reason to counterfeit – in the distant past and today – is usually fairly straightforward: the possibility of money for (almost) nothing, offset of course against the likelihood of getting caught and punished. However, the means of counterfeiting has changed, with rapid technological advances making counterfeiting arguably easier and reducing the amount of time that a currency remains resilient to counterfeiting. As a result, currency issuers have tended to release new currencies in shortening timespans in order to stay ahead of counterfeiters.

Early Counterfeiting

Counterfeiting predates the most common forms of physical currency used today, namely coins and banknotes. While it is difficult to pinpoint the very earliest form of money used, cowrie shells are a contender, having been used as currency as far back as 3300–2000 BC; they were also imitated using ivory, bone, clam shell and stone, and later bronze (Figure 1; Davies 1994; Peng & Zhu 1995).

Photo: Getty Images

Moving to more familiar forms of money, early coins were subject to counterfeiting via a range of different methods. Around 400 BC for instance, Greek coins were commonly counterfeited by covering a less valuable metal with a layer of precious metal (Markowitz 2018). Another method was to make a mould from a relatively low-value genuine copper coin, which was then filled with molten metal to form a counterfeit. The widespread practice of counterfeiting coins led to the rise of official coin testers, who were employed to weigh and cut coins to check the metal at the core.

Coin ‘shaving’ or ‘clipping’ was another commonly observed method of early coin fraud, whereby the edges of silver coins were gradually shaved off and melted down. In 17th century England, for example, the weight of properly minted money had fallen to half the legal standard, while one in 10 British coins was counterfeit (Levenson 2010). To remedy the situation, by mid 1690 all British coins had been recalled and reminted, and Sir Isaac Newton – the warden of the Royal Mint as well as the person who formulated the laws of motion and gravity – was tasked with stopping the situation re-emerging. By the end of 1699 he had successfully identified the lead counterfeiter as William Chaloner, who had produced counterfeits with a face value of £30,000 (worth around A$10 million today). He was ultimately hanged for his crimes.

Early paper banknotes were also counterfeited. Some of the first banknotes to be issued appeared in the Song Dynasty in China towards the end of the 10th century, and were known as ‘jiaozi’ (Von Glahn 2005). Initially jiaozi were issued privately by all manner of entities but, in 1005, the right to issue jiaozi was restricted by the authorities to 16 merchant houses. Complex designs, special colours, signatures, seals and stamps on specially made paper were used to discourage counterfeiters. Those caught counterfeiting faced the death penalty. Despite this, counterfeiting increased over time. This, along with an oversupply of jiaozi, led to inflation and in 1024 the right to print and issue currency was restricted to the government. The officially issued notes ‘expired’ after two years, after which they were redeemed, for a 3 per cent fee. This policy – perhaps the first ‘clean note’ policy in history – was in part aimed at preventing circulating currency from becoming too worn and tattered; having a higher quality of notes should make it easier to distinguish counterfeits from the genuine article. Some aspects of the evolution of the Song Dynasty's approach to note issue – such as moving from multiple issuers to just the government, having increasingly complex banknote designs and implementing a clean note policy – can be seen in modern banknote policy evolution 1,000 years later, including in Australia as discussed below.

The Pre-decimal Era in Australia

The earliest forms of paper money used in Australia were not fixed denomination banknotes as we know them today, but were more akin to promissory notes or personal IOUs. They were redeemable in coin and issued either by government authorities in exchange for produce, or by private individuals, with the latter often just hand-written on pieces of paper. The lack of any serious security features on these notes predictably led to forgeries. On 1 October 1800, the Governor of the Colony of New South Wales, Captain Philip King, noted that ‘[due to] the indiscriminate manner in which every description of persons in the colony have circulated their promissory notes … numerous forgeries have been committed, for which some have suffered, and others remain under the sentence of death’. While Governor King passed orders designed to regularise issuance, privately issued, hand-written notes continued to circulate, and be forged, in the years that followed (Vort-Ronald 1979).[2]

Banknotes proper were first issued in Australia in 1817 by the Bank of New South Wales, the forerunner of today's Westpac. Banknotes continued to be issued by various private banks (and the State of Queensland) throughout the 1800s. The proliferation of different notes made it difficult for the public to keep track of what was what, however, and counterfeiters made use of this by ‘converting’ low-value or worthless notes into what appeared to be relatively high-value notes (Vort-Ronald 1979). Eventually the authorities decided to standardise Australian banknotes. In 1910, the Australian Notes Act 1910 barred Australian states from issuing banknotes, with this responsibility transferred to the Commonwealth Treasury. Under the Bank Notes Tax Act 1910, commercial banks were strongly incentivised not to issue banknotes by means of a 10 per cent tax levied on their outstanding issue. In 1920, the sole responsibility for note issue was taken over by the government-owned Commonwealth Bank, the Reserve Bank's forerunner.[3]

Reserve Bank archives relating to banknotes begin around 1910 and already by 1921 a major counterfeiting event had been recorded. It was discovered that, in 1921, almost £3,000 (around $250,000 in current prices) in counterfeit £1 and £5 notes were circulating, corresponding to an estimated counterfeiting rate for those denominations in the order of hundreds of parts per million (compared with around 10 parts per million currently). Thomas S Harrison, the Australian Note and Stamp Printer, was apparently unsurprised, noting ‘the forgery … is of very poor workmanship and in my opinion has been manufactured by a criminal of a rather low type … a cleaner issue would minimise largely forged notes of this description being accepted … I cannot too strongly recommend the adoption of an engraved portrait in the design of Australian notes … I would reiterate my oft expressed opinion that the existing issue of Australian Notes, so far as design and character of work are concerned, are nothing more than what might be termed glorified jam labels’ (letter to the Secretary of the Commonwealth Treasury, 18 August 1921). Newspaper reports at the time record one Ernst Dawe, a goldminer from Kalgoorlie, charged in relation to the counterfeits: Dawe was ‘alleged to have introduced two Jugo-Slavs to a man who went under the name Jacobson … the accused was present when the man known as Jacobson paid the Slavs in forged bank notes for a large quantity of gold’ (‘Gold Dealing’, West Australian, 4 March 1922, p 7). The connection to the counterfeits was not proven, however, and Dawe was found not guilty.

The authorities appear to have taken on board a number of lessons flowing from this and earlier counterfeiting incidents. The Commonwealth Bank ceased its practice ‘of paying £4 to the Public and £3 to the Banks in respect of forged £5 Notes’ (letter from HT Armitage, Secretary, dated 15 June 1921), which had provided an incentive to counterfeit. To make counterfeiting more difficult, future banknote series typically contained at least one portrait.[4]

It is not uncommon for counterfeit manufacturers, once caught, to claim that the counterfeits they made were for promotional or other innocent purposes, and not made to be passed off as genuine. Even if true, manufacturing such copies is against the law, in part because no matter the original intended purpose, the counterfeits can still end up being passed off as genuine money and deceiving people. A case from 1927 illustrates this. Lance Skelton, John Gillian, and Roy Ostberg were tried for printing £12,500 worth of counterfeits (around $1 million in current prices). They claimed that ‘the notes were crudely printed on one side. It was intended to use the other side for advertising purposes’ (‘Note conspiracy charges’, The Argus, 26 March 1927, p 35). The first two men were nonetheless convicted and sentenced to four years in prison with hard labour, while Mr Ostberg was acquitted.

Another interesting episode concerns not so much counterfeits, as the law criminalising them. Section 60T of the Commonwealth Bank Act 1920 stated that it was an offence to possess counterfeit money. In 1927 Albert Wignall pleaded guilty to possessing 21 forged £5 notes but maintained that he had found them and had not known that they were counterfeits. This is despite earlier telling police ‘cut my head off if I tell you [who gave them to me]’ (statement by police officer John James Keogh, 15 February 1927). The judge hearing the case described the relevant law as ‘ridiculous’ since ‘as the charge is framed, anyone who handled the notes in court is liable to be arrested and charged’, and ruled that one could not be convicted unless one had ‘guilty knowledge’ (‘Ridiculous Act Has Dangerous Side’, The Evening News, 29 April 1927, p 8). The current version of the relevant law, as contained in the Crimes (Currency) Act 1981, states that ‘a person shall not have in his or her possession counterfeit money … [this] does not apply if the person has a reasonable excuse’. A related prohibition against possessing equipment that could be used to make counterfeits, which as originally drafted in law would have captured all printing presses in the country and today could conceivably capture anyone who owns a desktop printer, has similarly been amended.

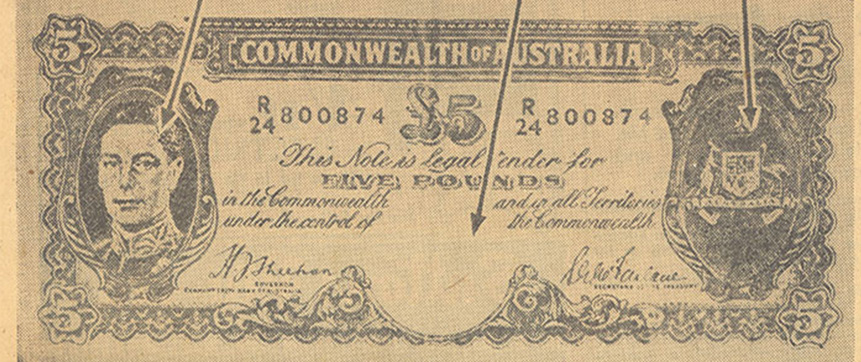

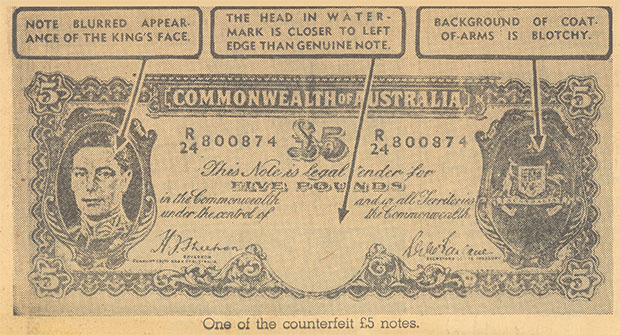

A loss of confidence in banknotes can have serious economic and social implications; this was especially true in the past when people were poorer (and so the loss flowing from unknowingly accepting a counterfeit was higher), the real value of banknotes was higher (the purchasing power of £5 in 1940 is around $400 in today's money), and there were no alternative payment methods to fall back on. This was demonstrated in 1940 when counterfeit £5 notes again became a major problem. A spate of hotels was defrauded and a large number of individuals were charged and convicted of passing forgeries. The police described it as ‘a determined gigantic attempt to defraud the public’ (‘Forged notes’, Sydney Morning Herald, 14 February 1940, p 8), and many workers and businesses refused to accept the £5 denomination (Figure 2).[5] While a number of individuals with many tens of notes – and who were therefore likely close acquaintances of the manufacturers – were caught and convicted, it appears that the manufacturers themselves were not caught. A police officer noted at that time that ‘The plant that produced them is probably at the bottom of the harbour by now’ (‘Many forged £5 notes still out’, The Daily Telegraph, 25 February 1940, p 5).

Source: ‘Huge counterfeit banknote coup’, The Sunday Telegraph, 28 January 1940, p 1

Australian Counterfeiting in the Decimal Era

The mid 1950s saw another spike in counterfeit £5 notes but, in 1966, Australia switched from pounds, shillings and pence to decimal currency. With this change, a new series of what were then state-of-the-art banknotes was introduced. The security features used on the new banknotes – including raised intaglio print and a metallic security thread embedded within the banknote substrate – were believed at the time to make them very hard to counterfeit, and so it came as a shock when one of the largest historical counterfeiting episodes in Australia followed less than a year later. In late 1966, forgeries of the new $10 note from what appeared to be a single counterfeiting syndicate began to appear in large numbers. It became known as the ‘Times Bakery’ counterfeiting incident, as the horizontal lines on the Times Bakery building on the counterfeits were not flush with the vertical edge of the building, as they should have been (Figure 3). These forgeries became a major issue, with police estimating at the time that $1 million worth – around $12.5 million in current prices, and equivalent to a counterfeiting rate of several thousand parts per million – were put into circulation, and numerous newspaper articles were written on the case (‘Police fear $1m in fake $10 notes’, The Sun, 26 December 1966, p 3).[6] In 1967, 10 defendants, five of whom came from the same family, were arrested and charged with manufacturing and distributing the fake notes in what was at the time a sensational case.[7] Seven of the accused were eventually found guilty and jailed, although their counterfeit notes appear to have still been turning up 11 years later (‘More dud notes turn up in shops’, The Daily Telegraph, 5 August 1977, p 9). One of the leading counterfeiters, Jeffery Mutton, wrote a manuscript while in prison, which was later unearthed and written about in the press (Shand, 2012). In the manuscript, Mutton revealed that he had been undone when Mutton's sister-in-law unknowingly used one of the counterfeits at her local corner store; the shop assistant suspected the notes weren't genuine, took down the sister-in-law's number plates, and alerted police. In his manuscript, Mutton wrote that his 10-year jail sentence was ‘small compared to the heartbreak, degradation and insecurity I have brought on my family’.

Source: https://museum.rba.gov.au/displays/polymer-banknotes/

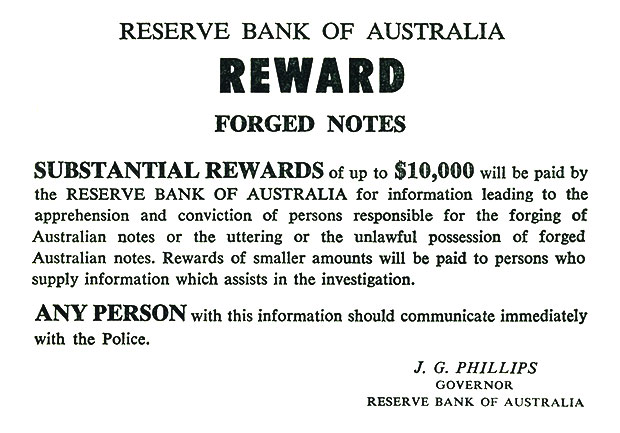

The Times Bakery incident prompted the Reserve Bank to offer a $10,000 reward for information leading to the apprehension and conviction of future counterfeiters (Commonwealth Treasury Press Release N. 941, 11 December 1967; Figure 4), while the lack of a well-coordinated police response led to public calls for the federal police to take over primary responsibility for the investigation of counterfeits from state police forces (Kennedy 1967). On 8 December 1967, the Attorney-General announced that Commonwealth Police Officers (the forerunner of today's Australian Federal Police (AFP)) would be assigned to combat counterfeiting on a full-time basis, with technical assistance from the Reserve Bank; this arrangement is still in place today. This counterfeiting incident also ultimately led to Reserve Bank-sponsored research by the CSIRO into how to make banknotes more secure, which, in turn, resulted in Australia's polymer banknote technology.[8]

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia, N-75-661

Selected International Episodes from Modern Times

Counterfeiters with access to a criminal network have, on occasion, made large profits producing high volumes of counterfeits, at least initially. Stephen Jory, an infamous British criminal who produced £300 million worth of fake perfume in the 1970s, is a prime example. After enhancing his criminal connections in prison, Jory and others set up an operation which manufactured counterfeit £20 banknotes in the garage of a house in Essex. Between 1994 and 1998, two-thirds of Britain's counterfeit money was produced by the gang – some £50 million in £20 banknotes. The counterfeits were of sufficiently high quality that in some cases they were redistributed through the banking system (Willis 2006; Woodward 1999). Jory and associates were nonetheless eventually caught and convicted.

Counterfeiters do not need to target high denominations of a currency to make a sizeable profit. The United Kingdom has experienced a significant issue with counterfeit £1 coins over the past two decades, with counterfeiting rates in the range of 2–3 per cent, even though the marginal profit from counterfeiting these coins is small.[9] In March 2017, in response to continuously high volumes of detections, the round £1 coin was replaced with a 12-sided £1 coin with new security features and, in October 2017, legal tender status was removed from the old coin. This example highlights that counterfeiters are willing to counterfeit low-value denominations if large-scale production and distribution is possible, forcing currency issuers to invest more in security features.

Counterfeiting can also have significant economic and political impacts, especially when counterfeits are indistinguishable from genuine banknotes. Portuguese counterfeiter Arthur Alves Reis was a case in point. In the 1920s, Reis forged a banknote printing contract and supporting letters purportedly from the Governor of the Bank of Portugal. He used these to deceive a London-based banknote printer, Waterlow & Sons, who held official Bank of Portugal printing plates. Waterlow & Sons used the official plates to print additional banknotes for Reis, which were collected in suitcases by an associate and transported by train to Portugal (Bloom 1966; Hawtrey 1932). Reis used Portugal's then-reputation for corruption, and the banknote printer's desire to secure new business, to convince the printer that the unusual arrangements were authorised by the central bank Governor. He ultimately convinced the printer to produce 580,000 500 escudo banknotes, worth almost 1 per cent of Portugal's nominal GDP at the time. Reis founded a commercial bank in Portugal using the proceeds, and made investments including mines in Angola and purchases of Bank of Portugal shares (the aim of these share purchases was to gain control of the privately owned central bank and then retrospectively regularise the print run). The apparent easy success of Reis's bank raised envy and suspicion, which ultimately led to Reis's arrest (Kisch 1932). The uncovering of the plot (rather than the counterfeits themselves necessarily) contributed to the collapse of the government and the installation of the Salazar dictatorship (Wigan 2004).

Another interesting example of counterfeiting occurred in Somalia. Somalia descended into civil war in 1991 and, for the next two decades, had no government. The population still needed a means of exchange, however, and this was provided for by an influx of counterfeits which, despite being easy to differentiate from ‘official’ currency, were accepted at face value (although the value of the currency fell to the marginal cost of printing a counterfeit, being a few cents). The stock of Somali shillings currently consists of a mix of official and counterfeit banknotes accumulated over the years, with 95 per cent of the local currency in circulation being counterfeit (IMF 2016; Koning 2013; Koning 2019).[10]

Counterfeiting as a Political Weapon

While counterfeiting is often motivated by financial gain, the ability of counterfeiting to have significant economic consequences has led to it being used as a political weapon. One example of this, although by no means the first, occurred during the American War of Independence from 1775 to 1783, when the British manufactured counterfeits of Continental currency on a boat anchored in New York harbour (Rhodes 2012).[11] These counterfeits were distributed through the colonies by those supportive of the British cause, which contributed to the devaluation of the currency by generating uncertainty about whether banknotes were genuine and by increasing the money supply.

During the Second World War, roles were reversed and Britain was the target of two secret counterfeiting operations, Operation Andreas and Operation Bernhard (NBB 2011). In particular, the German Government first planned to drop counterfeit pounds on the British Isles to create hyperinflation, but later changed plans to use the counterfeits to purchase supplies and further the German war effort. The Germans were quite successful in replicating the currency and using the forgeries, but the British authorities were alerted and ceased to issue denominations greater than five pounds as a precautionary measure. Most of the forged notes appear to have been destroyed by the defeated Germans at the end of the war. Nonetheless, it was not until 1970 that the £20 note was reissued by the Bank of England.

However, counterfeits manufactured overseas are not always an attack on sovereignty. For example, the 2011 United States Department of State Money Laundering and Financial Crimes Report (USDoS 2011) noted that India faced an increasing inflow of high-quality counterfeit currency from Pakistan. The report made clear that this activity was undertaken by criminal networks rather than any government, and was done for financial gain, but still noted the potential threat to the Indian economy.

New Challenges in Counterfeit Deterrence

Currency issuers and counterfeiters have always been locked in a battle of innovation, where issuers develop new security features and banknote series to make counterfeiting more difficult – with Australia's new Next Generation Banknote upgrade program an example of this – while criminals look for new techniques to help them counterfeit. The advance of modern technology is making counterfeit manufacturing more accessible, however, and law enforcement agencies such as Europol have noted a reduction in counterfeiters' need for ‘years of skilled apprenticeship and access to expensive professional printing equipment’ as they have moved from traditional to digital production methods (Europol 2014). This has shortened the timeframe over which currency issuers must respond.

The rise of the internet and the darknet has also allowed for new counterfeit distribution strategies, with counterfeit manufacturers sometimes selling their wares online. This allows the manufacturer to remain separate from distribution activities. It also means that multiple active distributers of the same counterfeit type may have no apparent link. One example of such an operation was uncovered in China in 2016 (Wei 2016). Partially manufactured counterfeit yuan were sold online by wholesalers. Those purchasing the counterfeits would finish the manufacturing process and then attempt to pass the counterfeits, although often unsuccessfully, with police making a number of arrests and seizing over CNY4 million (worth around A$1 million) in counterfeits and over 600kg of paper for future counterfeit production in this particular case (capable of making an estimated CNY100 million).

Responding to Counterfeit Attacks

Law enforcement response

Law enforcement agencies play a key role in responding to counterfeiting, and many have it explicitly included in their remit. The United States Secret Service (USSS) was originally founded in 1865 for the purposes of combating high levels of counterfeiting following the American Civil War (USSS 2018). Similarly, for international law enforcement agencies such as Europol and Interpol, counterfeiting remains a common crime area. In Interpol's case, uncovering counterfeiting was also part of its original mandate. These agencies provide their member countries with a range of services, including access to counterfeit data and counterfeit detection training.

National law enforcement agencies also routinely engage in joint operations to combat cross-border counterfeit crime. For example, in March 2014, Europol, the USSS, and the Spanish and Colombian police raided seven premises in Bogota, Colombia. They arrested six criminals and seized counterfeiting equipment and large volumes of counterfeit euros, US dollars and Colombian pesos valued at over 1.6 million euros (Europol 2014). Australia has benefited from such operations in the past. In 2006, a joint investigation between the USSS, the AFP and Colombian authorities disrupted a counterfeiting operation that had begun manufacturing Australian dollar counterfeits on polymer (‘Counterfeit Aust notes seized in Colombian raid’, ABC, 24 May 2006; RBA 2006). The raids uncovered sufficient material to produce counterfeits with a face value of up to A$5 million.

Focusing on just Australia, the AFP and state police forces regularly investigate and shut down local counterfeiting operations and prosecute those involved; see Ball (2019) for a discussion of recent trends in counterfeiting in Australia and the role of law enforcement in combating counterfeiting.

Central bank responses

In response to rising counterfeit threats, most central banks regularly update their banknotes to include improved security features that are harder to counterfeit. De La Rue, one of the world's largest banknote manufacturers, notes on its website that it produces new banknote designs for around 40 countries each year.[12] Many central banks also invest in counterfeit deterrence activities, including in research and development of new security features, and in counterfeit analysis centres to analyse and identify counterfeits. Central banks also work together where it makes sense to do so.[13]

Central banks also work with other stakeholders, such as manufacturers of banknote processing equipment, to combat counterfeiting. Many central banks – including the Reserve Bank – make counterfeits available to these manufacturers to allow them to check that their machines can accurately authenticate banknotes. Some central banks, such as the European Central Bank (ECB), go further, publishing the results of testing on their website and regulating the types of machines that can be used for processing banknotes (ECB 2010).

Conclusion

Counterfeiting has a rich and varied history going back to the very earliest forms of money. It has been pursued for personal gain – although at the significant risk of jail time, or, in the past, death – as well as for economic and political destabilisation by hostile countries. Both high- and low-value denominations are liable to be attacked. Currency issuers and counterfeiters are, and always have been, locked in a battle of innovation, with government authorities adapting and innovating in order to deter counterfeiting. Acceleration in the rate of technological development, however, seems to have shortened the timeframe over which each new security feature remains counterfeit-resistant and, in response, currency issuers are having to upgrade their banknotes and coins more frequently to ensure that counterfeiting remains low.

Regarding Australia, government and Reserve Bank policies concerning banknote issuance have evolved over time, with past counterfeiting episodes playing a major role in this change. Early banknotes were issued by multiple banks, contained few security features and were often worn and tatty, making the passing of counterfeits relatively easy. Today the Reserve Bank is the sole banknote issuer and has in place a system of incentives that serve to ensure that dirty and worn banknotes are removed from circulation. Australian banknotes are among the most secure in the world; and absent banknote upgrades (as are currently taking place), there is typically only a single series of banknotes circulating. Past policies of paying for counterfeits served to encourage their manufacture, whereas now counterfeits are recognised as worthless. And on the law enforcement side, badly drafted laws, which potentially could criminalise every printer in the country, have been amended. It has also been recognised that federal oversight of counterfeit policing can be beneficial; this resulted in the establishment of a team within the AFP dedicated to counterfeit deterrence.

Footnotes

The authors are from Note Issue Department and would like to thank Andrea Brischetto, Sani Muke and James Holloway for helpful comments and suggestions, as well as the Bank's Archives staff for help with historical documents. [*]

In fact, counterfeits may have been around before money: in early agricultural societies, records of exchanges were kept. These records were often sealed up inside an envelope of clay on which the information was duplicated. This extra precaution suggests that fake records also circulated (we thank Professor Bill Maurer for pointing this out). [1]

Given that the Colony of New South Wales was founded as a penal colony, and that a significant number of convicts transported to the colony were indeed forgers – including most famously Francis Greenway – it should perhaps come as no surprise that counterfeiting was an issue for the authorities. [2]

The Reserve Bank Act 1959 separated the central banking function of the Commonwealth Bank into the new Reserve Bank of Australia, while the commercial banking function became the responsibility of the Commonwealth Banking Corporation, known today as the Commonwealth Bank. [3]

Although even in 1937 a representative of the National Bank of Australasia wrote to the Commonwealth Bank seeking reimbursement for a counterfeit and noting that ‘when this bank was issuing its own notes, any such forgery was promptly considered a liability of the bank, and the presenter was reimbursed with the amount’. Letter dated 9 October 1937. [4]

For example, the assistant secretary to the Royal Agricultural Society, a Mr AW Skidmore, stated that £5 notes would not be accepted at the Royal Easter Show, and ‘ … in view of recent events, I advise people with £5 notes to change them before they go to the Show.’ (‘Won't take £5 notes at Show’, The Daily Telegraph, 28 February 1940, p 7). Workers also objected to being paid in £5 notes (‘Object to £5 notes in pay’, The Daily Telegraph, 31 January 1940, p 1). [5]

In hindsight, it appears that the $1,000,000 estimate was too pessimistic, with $119,720 worth of $10 counterfeits having been detected and removed from circulation by 1974. [6]

The case involved allegations of police brutality (‘a 20-year-old girl was slapped in the face and her fiancé, 19, was handcuffed to a chair and kicked in the shins during police questioning’; ‘Assaults alleged in fake $10 case’, The Herald (Melbourne), 10 March 1967, p 2) and a ‘how-to’ manual for passing counterfeits (‘Hints list issued with $10 fakes’, The Age, 10 March 1967, p 3). [7]

See <https://csiropedia.csiro.au/polymer-banknotes/> for a brief history of this research. [8]

That is, the counterfeiting rate was 20,000 to 30,000 parts per million (ppm), compared with a current Australian counterfeiting rate of around 10 ppm; Royal Mint 2016. [9]

An interesting side point to the Somali case is the light it sheds on what makes fiat currency valuable: in this case it can't have been government dictate to pay taxes in that money, as the currency continued to be used despite there being no government for two decades. [10]

See also Cooley (2008) for further discussion. [11]

Although this may also include numismatic products such as commemorative banknotes; see <https://www.delarue.com/markets-and-solutions/state-manufacturing-and-direct-sales>. [12]

For example the Central Bank Counterfeit Deterrence Group is a group of 32 central banks and note printing authorities which investigates the common emerging threats to the security of banknotes and proposes solutions for implementation by issuing authorities; see <https://rulesforuse.org/en>. [13]

References

Ball M (2019), ‘Recent Trends in Banknote Counterfeiting’, RBA Bulletin, March, viewed 1 August 2019. Available at < https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2019/mar/recent-trends-in-banknote-counterfeiting.html>.

Bloom M (1966), The Man Who Stole Portugal, Charles Scribner's Sons, New York.

Cooley, J (2008), Currency Wars: How Forged Money Is the New Weapon of Mass Destruction. Skyhorse Publishing, New York.

Davies G (1994), A History of Money: From Ancient Times to the Present Day, University of Wales Press, Cardiff.

European Central Bank (2010). ‘Decision of the European Central Bank of 16 September 2010 on the Authenticity and Fitness Checking and Recirculation of Euro Banknotes’, ECB/2010/14, Official Journal of the European Union.

Europol (2014), ‘International police operations busts Colombian currency counterfeiters’. Press Release, 17 March.

Hawtrey (1932), ‘The Portuguese Bank Note Case’, The Economic Journal, 42 (167), pp 391–398.

IMF (2016), IMF Country Report No. 16/136.

Kennedy T (1967), ‘Counterfeit points to Federal police gaps’, Australian Financial Review, 6 January, pp 1, 4.

Kisch C H (1932), The Portuguese Bank Note Case, Macmillan and Co., London.

Koning JP (2013), ‘Orphaned currency, the odd case of Somali shillings’, blog post. Available at: <http://jpkoning.blogspot.com/2013/03/orphaned-currency-odd-case-of-somali.html>

Koning JP (2017), ‘Bringing back the Somali shilling’, blog post. Available at: <http://jpkoning.blogspot.com/2017/03/bringing-back-somali-shilling.html>

Levenson T (2010), Newton and the Counterfeiter, Faber and Faber, London.

Markowitz M (2018), ‘Bad Money – Ancient Counterfeiters and Their Fake Coins’, Coinweek, 24 July.

National Bank of Belgium (NBB) (2011), ‘A Nazi Counterfeit in the National Bank’. Available at <https://www.nbbmuseum.be/en/2007/11/a-nazi-counterfeit.htm>.

National Research Council (2006), Is That Real? Identification and Assessment of the Counterfeiting Threat for U.S. Banknotes. The National Academies Press, Washington DC.

Peng K and Zhu Y (1995), ‘New Research on the Origin of Cowries in Ancient China’, Sino-Platonic Papers, 68, pp 1–26.

Reserve Bank of Australia (2006), Annual Report 2006. Available at <https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/annual-reports/rba/2006/pdf/2006-report.pdf>

Rhodes K (2012), ‘The Counterfeiting Weapon’, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Region Focus, First Quarter, pp 34–37.

Royal Mint (2016), The Royal Mint Limited Annual Report 2015–16.

Shand, A (2012), ‘The money changers’, The Australian, 8 June.

United States Department of State (USDoS) (2011), International Narcotics Control Strategy Report Volume II Money Laundering and Financial Crimes, March.

United States Secret Service (USSS) (2018), ‘150 Years of Our History’, USSS Website, viewed 20 April 2018. Available at: <https://www.secretservice.gov/about/history/events/>.

Von Glahn R (2005), ‘The Origins of Paper Money in China’, in Goetzmann W and Rouwenhorst K (eds), The Origins of Value: The Financial Innovations that Created Modern Capital Markets, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Vort-Ronald M (1979), Australian Banknotes.

Wei C (2016), ‘Police Break Up Counterfeiting Ring; 14 Held’, China Daily, 15 April.

Willis T (2006), ‘Stephen Jory’,The Independent, 27 May.

Wigan H (2004), ‘The effects of the 1925 Portuguese Bank Note Crisis’, Economic History Working Paper No. 82/04, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Woodward W (1999), ‘Counterfeiters printed £50m in fake notes’, The Guardian, 23 December.