Bulletin – June 2022 Payments What Can You Do With Your Damaged Banknotes?

- Download 3.6MB

Abstract

Through the Reserve Bank's damaged banknote claims service, members of the public can ask for their damaged banknotes to be assessed and the value redeemed. Removing poor-quality banknotes also supports the Bank's aim of ensuring that the public has confidence in Australian banknotes as a means of payment and a secure store of wealth. This article provides an overview of the service, its key users and the circumstances in which claims are lodged. While the value of the majority of claims is relatively low, claims containing banknotes damaged in storage can be significant, reflecting the role of cash as a secure store of wealth.

Introduction

The Reserve Bank aims to have only good-quality banknotes in circulation. High-quality banknotes make it more difficult for counterfeits to be passed or remain in circulation, and help to minimise problems in banknote accepting or dispensing equipment. However, due to mishaps and natural disasters, banknotes can become damaged beyond normal wear and tear, making them unsuitable for transactions or as a store of wealth. Damaged banknotes include those with significant pieces missing, with excessive damage from heat or other environmental factors, or that have become contaminated.

When presented with such banknotes, authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) may be unable to reimburse holders with the full value. This may be due to uncertainty of their value, or health and safety concerns with the handling of the banknotes.

For many years, the Reserve Bank has offered a free claims service to eligible holders of damaged Australian banknotes to ‘redeem’, or be reimbursed, their value.[1] By removing damaged banknotes from circulation, the service also supports the Bank's objective of maintaining good-quality circulating banknotes.[2] Claims for damaged banknotes can be lodged through ADIs, which will forward them to the Bank. Once received, the Bank assesses the damaged banknotes in accordance with its Damaged Banknotes Policy. More information about the Policy and how to redeem value for damaged banknotes can be found on the Reserve Bank's website.[3]

Recent trends in claims

Between 2014 and 2021, the Reserve Bank processed around 110,000 damaged banknote claims and made $44 million in payments – an average of around 14,000 claims worth $5.5 million each year (Graph 1). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of claims processed fell significantly, to an average of around 10,000 claims per year in 2020 and 2021. The reduction in the number of claims in 2020 likely reflects the pandemic-related lockdowns that restricted people's movements and their ability to transact with cash. The significant increase in the value of claims paid in 2021 can be attributed to two high-value bank claims: one through a foreign exchange bureau;[4] and the other from a fire-affected branch.

Who uses the claims service?

The claims service is accessed by a set of diverse users, including individuals, businesses, government organisations and professional cash handlers (e.g. ADIs, cash-in-transit companies (CITs) and operators of automated teller machines (ATMs)). Government organisations include the police who, during the course of performing their duties, can come into possession of damaged banknotes or cause banknotes to be damaged (e.g. by forensic analysis). ADIs, CITs, major businesses and the police tend to make a higher number of claims as they encounter damaged banknotes more frequently than individuals, who tend to only make one-off claims.

Between 2014 and 2021, claims from individuals constituted around two-thirds of the total number of claims, but only 25 per cent by value (Table 1). This reflects that most claims from individuals typically consist of single banknotes. By contrast, claims by ADIs and CITs combined constituted 15–20 per cent of the total number each year, but around 60 per cent by value. CITs tend to batch together the damaged banknotes identified during processing of customer deposits, prior to submitting a claim to the Reserve Bank. A mishap, such as a flooding event, affecting an ADI or CIT site can also involve a significantly larger volume of damaged banknotes. Although police claims were relatively infrequent, a few made between 2014 and 2021 were of high value.

The vast majority of claims processed were from claimants based in Australia. However, between 2014 and 2021, the Reserve Bank paid around 80 claims from claimants in approximately 30 foreign countries, worth $422,000, excluding one unusually large claim via a foreign exchange bureau. Overseas claims are typically lodged by individuals holding Australian banknotes from previous travel, banks/foreign exchange bureaus, and government organisations operating in countries where Australian banknotes are used for day-to-day transactions.[5]

| Category | Number of claims | Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (‘000) | Per cent of total |

($ million) | Per cent of total |

||

| Individuals | 72.5 | 65 | 11.1 | 25 | |

| Businesses & other | 18.5 | 17 | 3.4 | 8 | |

| ADIs(a) | 12.6 | 11 | 11.0 | 25 | |

| CITs | 7.1 | 6 | 16.2 | 37 | |

| Police | 0.7 | 1 | 2.3 | 5 | |

| Total | 111.5(b) | 100 | 44.1(b) | 100 | |

|

(a) Includes overseas financial institutions. Source: RBA |

|||||

Types of damage to banknotes

The circumstances under which claims for damaged banknotes arose during this period were diverse. For the purpose of this article, we have used four broad damage classifications: ‘torn or ripped’; ‘heat’; ‘environment’; and ‘contamination’. These four classifications constituted the vast majority of claims received (Graph 2).

Torn or ripped banknotes

Torn or ripped banknotes are ‘incomplete’ banknotes that have significant pieces missing (Figure 1). Generally, payment for an incomplete banknote is proportional to the part of the banknote remaining.[6] In this way, the combined value paid for all the pieces, were they to be presented, would be the face value of the original banknote. When lodging a claim for incomplete banknotes, the claimant should include as many of the remaining banknote pieces as possible to ensure that the largest value can be paid.

Between 2014 and 2021, claims for torn or ripped banknotes constituted over one-half of claims received and one-fifth by value. The most common claim scenario was where a claimant had accidentally torn their banknote, and lost a part of it. Claimants may also have inadvertently come into possession of torn or ripped banknotes during a transaction with cash, such as when receiving change. The mix of claims for torn or ripped banknotes differed from the mix for damaged banknotes overall – CITs accounted for a higher share of the value of claims, and businesses and ADIs a lower share. The breakdown of the claims made during this period is as follows:

- Claims from individuals constituted almost two-thirds of all claims for torn or ripped banknotes received (Graph 3). However, these accounted for only a small proportion of the value of claims as most were for a single banknote.

- Submissions from businesses and ADIs accounted for around 30 per cent of all claims for torn or ripped banknotes, but each accounted for 5 per cent or less by value.

- There were relatively few torn or ripped claims submitted by CITs. However, these represented the majority of the value of payments for this damage category as CITs typically batch their torn or ripped banknotes and lodge them as a higher-value claim.

Heat-damaged banknotes

Heat-related claims are relatively common, typically accounting for over 30 per cent of claims by both number of submissions and value. Banknotes may shrink, burn or melt, due to heat from appliances, building fires, bushfires and other heat sources (Figure 2). In cases where the banknotes have become severely damaged, the Reserve Bank's ability to accurately assess the claim will be improved if the claimant has collected as much banknote debris as possible – including the container they were stored in if it is unable to be separated without loss of banknote material.

Between 2014 and 2021, the majority of heat-related claims were from individuals, representing around half of the value of payments for this damage category – and accounting for one-fifth of the total value of all payments made.

The bulk of heat-related claims were typically due to damage by household appliances. The following are some examples:

- It was common for claimants to report that they accidentally burnt their banknotes in kitchen/electrical appliances (e.g. oven, toaster, light fittings) where they were intended to be temporarily stored or hidden.

- There were instances where banknotes were accidentally damaged while the individual performed an activity, such as leaving banknotes in clothing that was then placed in the dryer or ironed, attempting to dry wet banknotes or placing them too near to a heat source.

- After the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, several claimants indicated that they had used heat – including microwaving, boiling or using a hair dryer – in an attempt to sanitise the banknotes as a precaution, but damaged them in the process.

Heat damage can also occur to banknotes held in storage; such claims tend to be higher in value. Between 2014 and 2021, there was an average of around 50 house fire claims per year, representing 1 per cent of the number of heat-related claims, but accounting for around 15 per cent by value. There were also around four bushfire claims each year, though this number increased significantly during major bushfire events, as was experienced following the 2019–2020 bushfires (see below).

The motives for lodgement of claims by businesses are similar to those of individuals. Businesses may unwittingly receive heat-affected banknotes from customers during transactions, or accidentally damage their banknotes via heat from appliances (which is common for a restaurant business) or as a result of a building fire. There have also been a few instances of fires affecting ATMs, in which banknotes have fused to internal components of the ATM. While lodgements by CITs between 2014 and 2021 accounted for less than 5 per cent of all heat-related claims, by value they accounted for around one-quarter of payments made; as with torn or ripped banknotes, CITs will typically batch together the damaged banknotes before making a claim.

Australian 2019–2020 bushfire claims

There was a large increase in the number and value of bushfire claims received by the Reserve Bank as a result of the 2019–2020 bushfires in Australia; as at the end of 2021, a total of 57 claims valued at around $475,000 had been received and settled. Of those claims:

- 49 claims were from New South Wales, four from Queensland, two from Victoria, and two from South Australia

- 53 claims worth around $440,000 were lodged by individuals (mainly banknotes burnt while stored at home), one low-value claim was lodged by a small business, and three claims were lodged by banks (received as deposits)

- an equivalent of 7,300 banknotes were assessed, with 90 per cent of the claims for $50 and $100 banknotes, reflecting the role of high-denomination banknotes as a store of value

- payments ranged from small amounts to around $70,000, with a median value of $4,500.

The extent of damage to the banknotes varied from claim to claim, depending on how the banknotes were stored at the time of the bushfires (Figure 3). Banknotes stored in a fireproof safe sustained some degree of shrinkage and minor burns. In situations where the banknotes were not stored in a fireproof safe, the banknotes had either melted, fused or burnt. Despite the extent of damage of these banknotes, the Reserve Bank was still able to use various techniques to assess their underlying value from the debris that was submitted.

Environmental factors

Banknotes can be damaged due to exposure to certain environmental factors, including the elements (such as the sun, dirt or water), animals (e.g. eaten by animals or insects) or harsh storage conditions (Figure 4). Environment-related claims also include banknotes affected by floods or other natural disasters that do not arise from heat. If the banknotes are showing signs of disintegration, claimants are advised to handle them with care and to package them carefully to prevent further damage or loss of banknote material. Banknotes that are affected by flood water must be sealed in packaging and clearly labelled as such so that any potential health and safety concerns can be appropriately managed.

Between 2014 and 2021, environment-related claims accounted for around 10 per cent of total submissions, but a significantly larger share by value. While most environment-related claims are made by individuals, these represent only a small share of the value of claims in this damage category. Some examples of environment-related claims by individuals received over the period are provided below:

- A few high-value claims were for banknotes that were stored at home, usually over an extended period. One common category was deceased estate claims for banknotes found on properties. These claims often consisted of old paper series banknotes that had disintegrated from excessive exposure to water or become soiled from being buried.

- The circumstances under which low-value claims were made were diverse; however, a number of claims arose from polymer banknotes that had been accidentally left in the sun (and forgotten for an extended period), making them brittle when handled.

- While uncommon, some claims involved banknotes that exhibited extensive ink wear due to constant friction and perspiration from being stored in the claimant's shoes.

By volume, total submissions by ADIs and CITs accounted for around 5 per cent of all environment-related claims, but represented around 75 per cent of the value paid.

In those years where major floods occur, claims by ADIs, CITs and businesses involving flood-affected banknotes can account for a significant proportion of claims by value, across all user and damage categories.[7] In the aftermath of Cyclone Debbie in early 2017, several high-value claims were lodged by ADIs, CITs and major retailers (see below). Assessment of claims from the 2022 Queensland and New South Wales floods are still in progress; as at 3 June 2022, payments totalling $6.9 million have been made for over 70 claims.

Water damage caused by events other than natural floods (e.g. leaks or moist storage conditions) can also result in high-value submissions by CITs and ADIs. In 2021, a bank branch fire resulted in a claim for banknotes that were wet from an automatic sprinkler system.

By value, the majority of claims for banknotes damaged by animals since 2014 have been related to mice infestations on sites where ATMs were located. Following the mice plagues covering parts of eastern Australia in early 2021, two high-value claims for banknotes damaged by mice in ATMs were lodged. There were also cases of individuals' banknotes being damaged by mice and other rodents, although their values were much lower.

Environment-related claims from the police are rare; however, when they do occur, they can be significant in value. Over 2014–2021, these claims were typically for banknotes that were seized or reported to the police following their discovery in a buried state.

Claims from Cyclone Debbie in 2017

In March 2017, a number of towns in New South Wales and Queensland were affected by floods caused by Cyclone Debbie. In the aftermath, the Reserve Bank received 32 flood claims and made a total of $3.3 million in payments. Payments on flood claims represented around half of the total value of claims processed in the 2017/18 financial year.

ADIs accounted for over half of the claims received. The remainder were by CITs, retail outlets and businesses that operate ATMs.

Around 92,000 banknotes were processed, mostly of the $50 and $20 denominations (which accounted for 55 per cent and 25 per cent of the banknotes, respectively), reflecting the key denominations used in ATMs.

Banknotes from flood claims are typically wet and sticky, requiring multiple counting iterations to ensure accurate assessment. To assist with the process, banknotes can be placed in a drying cabinet by Reserve Bank staff prior to assessment (Figure 5).

Contaminated banknotes

Contamination can occur when banknotes come into contact with bodily fluids (e.g. blood), chemicals and stains (Figure 6). As a general rule, all banknotes identified as contaminated are forwarded to the Reserve Bank's laboratory where they can be safely handled. For such claims, claimants are required to properly seal their banknotes and state the nature of the contaminant to assist management of any potential health and safety issues.

Between 2014 and 2021, contamination claims constituted 1 per cent of all claims by number and 8 per cent by value. The extent of claim lodgements for contaminated banknotes differed across user categories, as follows:

- Claims for contaminated banknotes were relatively infrequent among individuals and businesses, and usually involved cleaning agents, chemical spills or stains (e.g. from hair dye, pens) where the chemicals had removed or defaced the designs on the banknote.

- Submissions from CITs accounted for over one-third of contamination claims, and around one-half of the value paid. These claims often involved banknotes contaminated with unknown substances, as they were sourced from the CITs' commercial customers and lodged as contamination claims as a precaution.

- Claims containing banknotes stained by an anti-theft device can be lodged by banks, CITs and operators of ATMs. This can be the result of a robbery attempt, an accidental trigger of the device or testing of new equipment.[8] Over this period, the value of such claims was typically small for banknotes stained in a till, but larger for a safe or an ATM.

- Police claims accounted for a significant share of all contamination claims received, both by number of submissions and value. The banknotes had typically been subject to chemicals used in forensic analysis, exposed to illicit substances or removed from a deceased person. Around 60 contamination police claims were received a year, with each claim worth an average of around $2,000.

Assessment value

Between 2014 and 2021, around 75 per cent of claims assessed consisted of a single banknote. This resulted in a relatively low median value of payments of $25 over the full period, and around $30 in more recent years. Around 80 per cent of claims paid between 2014 and 2021 were valued at $50 or less. Torn or ripped banknote claims were typically low value (Graph 4), with a median value of $15. Heat and environment-related claims had a higher median of $50 each, while contamination claims had a median of $120. Despite relatively small median claim values, a small number of high-value claims – less than 4 per cent – accounted for a significant portion of all payments by value. Claims assessed at between $1,000 and $10,000 accounted for 25 per cent of the value of all payments, while claims over $10,000 accounted for 60 per cent of the total value of payments.

Conclusion

For many years the Reserve Bank has operated a damaged banknote claims service. This enables holders of damaged banknotes to redeem value provided their claims meet the Bank's criteria for payment. In particular, the claims service is available to people or organisations that have accidentally damaged their banknotes or inadvertently come into possession of damaged banknotes. In providing the service, the Bank undertakes due diligence to ensure only eligible claims are reimbursed – this reduces the risk that the service could be used for criminal purposes.

The median value of claims is typically low, at around $30. Most frequently, the service is used to remove torn or ripped banknotes held by individuals, which are often claims for single banknotes. However, where banknotes have been damaged in storage, their value can be large, reflecting the use of banknotes as a store of value. Natural disasters are a source of damage to banknotes, and lead to an influx of claims for reimbursement; claims related to bushfires most typically come from individuals, while businesses (and particularly financial institutions) tend to lodge a higher value of claims related to floods.

As well as providing reimbursement, the Reserve Bank offers the service as a means to remove poor-quality banknotes from circulation. This is an important aim of the Bank as good-quality banknotes help to maintain the confidence that the public has in banknotes as a means of payment and a secure store of wealth.

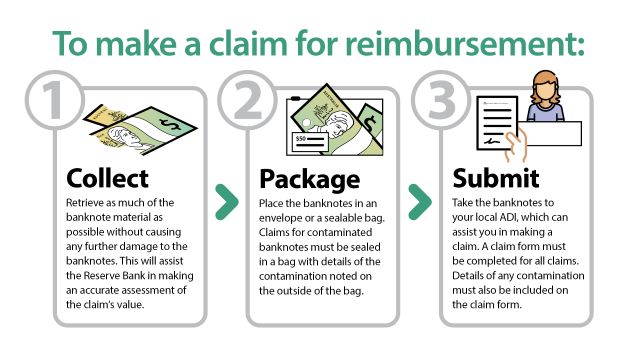

Box A: What can you do with your damaged banknotes?

If you have damaged banknotes, you can submit a damaged banknote claim. The Reserve Bank will determine the value of the damaged banknotes as per the Damaged Banknotes Policy and reimburse you the assessed amount.

Do not include any coins or foreign banknotes, as the Reserve Bank is unable to process them.

Further information on payment criteria and how to redeem value for your damaged banknotes can be found on the Reserve Bank's website.

Endnotes

The authors are from Note Issue Department. [*]

Based on Reserve Bank archives, the claims service has been in existence in one form or another since the 1920s. [1]

The Reserve Bank publishes a Banknote Sorting Guide to assist professional cash handlers fitness-sort banknotes. This helps them identify banknotes that are unfit for recirculation and, depending on the extent of the damage, when a damaged banknote claim should be lodged. See RBA, ‘Banknote Sorting Guide’. Available at <https://banknotes.rba.gov.au/assets/pdf/sorting-guide.pdf>. [2]

See RBA, ‘Damaged Banknotes’. Available at <https://banknotes.rba.gov.au/damaged-banknotes/>. The majority of claims submitted to the Reserve Bank are lodged via a branch of an ADI. Where submission through an ADI branch is not possible, claims can be posted to the Reserve Bank's designated address for the National Banknote Site, where claims are processed. [3]

The claim via the foreign exchange bureau consisted of extremely worn and soiled banknotes from overseas. Given the size of the claim, it would appear the banknotes had been accumulated over an extended period to optimise repatriation cost. [4]

These include, for example, Kiribati, Nauru and Tuvalu. [5]

Exceptions to this are if more than 80 per cent of the banknote remains then full face value is paid, and if less than 20 per cent is left then no value is paid. The Reserve Bank Assessment Grid can be used to estimate the value of an incomplete banknote. See, ‘Grids for Assessing Value of Australian Polymer Banknotes with Pieces Missing’. Available at <https://banknotes.rba.gov.au/assets/pdf/grids-polymer.pdf>. [6]

Individuals tend not to make as many claims after floods. This may reflect individuals' preference to clean their own banknotes if they can in order to use the cash in time of need. This may, however, not always be practical for professional cash handlers if a large quantity of banknotes is involved. [7]

The Reserve Bank's approval is required prior to using Australian banknotes for testing purposes. [8]