Bulletin – September 2020 Global Economy The Global Financial Safety Net and Australia

- Download 1MB

Abstract

The Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN) allows for financial assistance to be provided to economies in the event of an economic or financial crisis. Together with the substantial monetary and fiscal policy response globally, the GFSN has played a key role in helping economies respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. The GFSN has a number of elements, including the assistance provided by the International Monetary Fund, regional financing arrangements and some bilateral swap lines established by central banks. This article provides an overview of the GFSN, how it has evolved and been used over recent months, and the role the Reserve Bank of Australia plays in it. Use of the GFSN could increase materially over the period ahead if economic and financial market conditions around the world deteriorate.

Introduction

The Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN) allows for financial assistance to be provided to economies should they experience an economic or financial crisis that leaves them unable to meet external financing needs. The purpose of this assistance is generally to prevent a liquidity problem (in this context, a short-term foreign currency shortfall) from causing a solvency problem. If an economy is unable to meet their international payment obligations (such as debt repayments), its problems can easily spill over to other countries. This is one reason why most countries commit funds to the GFSN.

The GFSN has played an important role in response to the current COVID-19 crisis, particularly to support emerging and low-income economies. Alongside policy action by advanced economies, the support provided by the GFSN helped to ease the sharp tightening of financial conditions experienced in the immediate wake of the pandemic. This tightening of conditions had been particularly acute for emerging market economies (EMEs), where government bond yields rose significantly, equity prices declined, and exchange rates depreciated sharply alongside substantial portfolio outflows of equities and bonds (Graph 1). Drawing on the GFSN has also helped some EMEs and low-income countries meet urgent external financing needs arising from the pandemic and facilitated immediate additional health care spending. While financial conditions have improved, the challenges of the pandemic remain. The GFSN is likely to continue to provide an important source of stability to the global financial system over the period ahead, with its use potentially increasing materially if economic and financial market conditions around the world deteriorate further.

This article describes the size and characteristics of the different layers of the GFSN. It discusses use of, and changes to, the GFSN in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis. In addition, the article sets out the Reserve Bank's role in Australia's participation in the GFSN.

Layers of the GFSN

There are four distinct parts or ‘layers’ of the GFSN (Figure 1):[1]

- International reserves are foreign currency assets owned by country authorities and are generally thought of as the first layer of defence in a foreign currency liquidity crisis. Reserves include a country's official foreign currency holdings, gold holdings, Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) and reserve position at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (i.e. funds lent by a country to the IMF).[2] Reserves can be used to dampen volatility in a country's exchange rate, repay official sector international debts and provide foreign currency liquidity to the financial system during periods of stress.

- Bilateral swap agreements (BSAs) are agreements between two central banks.[3] They usually take the form of lending one currency in return for collateral (in the borrower's currency) plus interest. The funds lent are typically denominated in the local currency of the lender country, but can be in another currency (e.g. a reserve currency like the US dollar). Not all BSAs are part of the GFSN and, as we explore later in article, there is some debate as to where to draw the line on their classification. This issue notwithstanding, most BSAs have the effect of alleviating market stress and at a minimum can be thought of as a complement to the GFSN.

- Regional Financing Arrangements (RFAs) are financing arrangements between groups of countries to pool resources such that most members have access to more resources than they contribute. There is no single model for an RFA. For example, some RFAs use central bank foreign exchange reserves to fund lending, while for others the governments may provide the full amount of funds.

- The IMF provides financial assistance in the form of loans or credit lines often with specific conditions attached (these conditions relate to policy measures that the recipient must implement to receive the funds); almost all countries are members of the IMF and most contribute financial resources to fund lending. For these reasons, the IMF is often referred to as the ‘centre of the GFSN’.

Source: RBA

The layers of the GFSN differ along a number of dimensions, including purpose, cost, ease of use, size and access.

Purpose

There are three main types of crises that the GFSN attempts to mitigate (Denbee, Jung and Paternò 2016).

- A balance of payments (BoP) crisis in which countries lack (or potentially lack) the financing needed to meet international payment obligations. This may be due to unsustainable domestic policies, natural disasters (including health disasters like pandemics) or other sudden changes in market conditions such as commodity price shocks (IMF 2020a).

- A foreign currency (FX) liquidity crisis in which banks or other financial system participants cannot access adequate short-term funding in foreign currency (typically a reserve currency such as the US dollar).

- A sovereign debt crisis in which governments are shut out of debt markets because investors are unwilling to lend. This could be due to a range of factors including levels of public debt that are perceived as unsustainable or heightened global risk aversion.

In practice, these types of crises are not necessarily independent of one another and can be concurrent. For instance, at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, uncertainty and risk aversion led to market volatility and high demand for US dollars which limited market participants' access to funding in US dollars (an FX liquidity crisis). At the same time, COVID-19 has also caused some countries to experience sharply lower net foreign income, causing BoP pressures. These crises can also occur alongside other types of crises (such as banking crises).

Only the IMF and a country's own reserves are available to respond to all three types of crises (Table 1). By contrast, use of BSAs and RFAs depends on the parties involved and the terms of the specific agreement. For example, most BSAs are only available for use in FX liquidity crises; BSAs that are supported by, or done on behalf of, a signatory's government can sometimes be used for a BoP crisis.

| BoP crisis | FX liquidity crisis | Sovereign debt crisis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reserves | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| BSAs | In some cases(a) | Yes | No |

| RFAs | Yes | Yes | In some cases(b) |

| IMF | Yes | Yes | Yes |

|

(a) BSAs that are supported by, or done on behalf of, a signatory's government

can sometimes be used for a BoP crisis.

Sources: RBA |

|||

In many cases, the primary purpose of a central bank swap line is to support market functioning and mitigate financial stability risks domestically (including where risks arise due to spillovers from foreign markets). It is also the case that swap lines are not extended to all economies. These attributes reflect the fact that when establishing a swap line, a central bank must consider its mandate and risk tolerance, which typically does not stretch to alleviating BoP or other types of crises in other countries. This notwithstanding, swap lines can in practice provide an important financial safety net to other countries.

For this reason, it is debatable whether some BSAs – such as swap lines issued by the US Federal Reserve and some of the major currency issuers – should be considered part of the GFSN. For the purposes of the analysis in this article, we have included swap lines that can mitigate an FX liquidity crisis, even when they were extended primarily to address domestic financial market issues. However, we have identified these separately in tables and graphs. More broadly, in our definition of the GFSN we have included BSAs that have at least one of the following characteristics: are in a reserve currency; issued by the People's Bank of China (PBC); sponsored by a finance ministry; or specifically intended to address BoP issues.[4] BSAs that do not have at least one of these characteristics are likely to be of limited use in the three types of crises listed above, and on this basis are excluded from our definition of the GFSN.

Cost

In normal times (i.e. outside a crisis), reserves are the most expensive layer of the GFSN. This is because countries pay a cost of carry to hold them and also may be required to allocate capital against the risk of valuation losses associated with their holdings.[5] In this context, reserves provide self-insurance against a crisis. By contrast, RFAs and the IMF are mutualised insurance; they allow countries to pool resources such that in a country-specific crisis, each member can generally access more emergency assistance than they commit to lending. This means that the cost of these types of insurance are lower than for reserves.

Ease of use and robustness

While reserves are expensive, they are easy for a country to use since it has direct control over them. In comparison, for a loan from the IMF the country must go through an application process and may also be required to meet specific conditions set by the IMF.[6] The ease of access to RFAs varies by the specific arrangement. Some large RFAs allow access to funding below a moderate limit without conditions, but above that limit require an IMF program to be in place before funds can be provided. BSAs are easier to use than IMF funding or RFAs due to the lack of conditionality to access funds once a BSA has been agreed. However, access to BSAs are limited as they are extended at the discretion of central banks and/or governments, as discussed above.

Size of and Access to the GFSN

The lending capacity of the GFSN has grown significantly over the past two decades, and is now equivalent to around 20 per cent of world GDP.[7] In particular, since the global financial crisis (GFC) RFAs and BSAs have become much more widespread, and the value of swap lines has increased considerably (Graph 2). This strong growth in the GFSN is partly because of the strong economic growth of EMEs, and the desire of many of these economies to improve their resilience to risks arising from the volatility of capital flows. Indeed, EMEs and developing economies as a proportion of the global economy have grown from around 40 per cent in the early 1990s to almost 60 per cent in 2019.

Reserves

By value, reserves are the largest component of the GFSN, amounting to more than US$13 trillion as of mid 2020. Access to reserves varies significantly across regions. In particular, EMEs in Asia have accumulated reserves at a much faster rate than other regions to build up self-insurance in the wake of the Asian Financial Crisis (Stevens 2007). This growth has slowed in recent years (Graph 3). Most large EMEs have accumulated a level of reserves that exceeds the minimum threshold for what the IMF considers to be adequate.[9]

International Monetary Fund

The rest of the GFSN is worth around one-third of the value of reserves, amounting to almost US$5 trillion. Of this, the IMF accounts for US$1.3 trillion. The primary source of IMF funds are the ‘quota’ contributions made by member countries, which are a form of paid-in capital. Some countries also contribute to the IMF via lending arrangements; under these agreements, member countries essentially promise to lend funds to the IMF if required.[10] The level of IMF funding has not changed materially since 2012, though in 2020 countries agreed to an increase in the size of lending arrangements, which is expected to become effective in 2021.[11]

The IMF provides a number of different lending facilities that cater to a range of country circumstances and shocks (Table A1). For most IMF facilities, the funding limits are determined as a proportion of a country's quota contribution. The quota share of each country attempts to reflect their relative importance in the world economy, but over time quotas have become less representative of countries' position in the world. This is because some economies have grown more quickly than others, and updates to quota have not fully kept pace with this change.[12] In particular, economies in the Asian region have lower access to IMF funding relative to countries in other regions due to the pace of growth in the Asian region in recent years (Graph 4).

Offsetting their relatively limited access to IMF funding, EMEs in Asia have access to more external funding through BSAs and RFAs, and have built up larger reserve buffers than countries in other regions. In comparison, the IMF remains the primary or only external source of financing support for many EMEs outside Europe or Asia. In particular, EMEs across the Middle East, Central Asia and Africa have lower access to external funding; reserve buffers in these economies are also, on average, lower than in other regions.

Bilateral swap agreements

By value, swap lines currently account for an estimated US$2.5 trillion of the total size of the GFSN. Around half of this amount is provided by the US Federal Reserve and other reserve currency issuers specifically to mitigate strains in cross-border funding markets (that is, for FX liquidity crises) that could spill over to affect the domestic markets of the reserve currency issuers (Table 2).

As mentioned earlier, some BSAs are potentially available for BoP crises, but these swap lines are mostly sponsored or endorsed by a government entity. The two largest providers of these swap lines are the PBC and the Bank of Japan (backed by the Japanese Ministry of Finance). These swap lines have only been used to a limited extent and are therefore largely untested.

|

Value

US$ billion |

Number | Purpose | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reserve currency issuers(a) | 713 | 15 | FX liquidity only |

| Federal Reserve (other) | 450 | 9 | FX liquidity only |

| People's Bank of China(b) | 1,042 | 34 | Cooperation or promotion of trade/investment; financial stability(c) |

| Bank of Japan(d) | 224 | 6 | Financial stability; cooperation or promotion of trade/investment; foreign currency liquidity |

| Other | 48 | 13 | Various |

|

(a) Swap lines between the US Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan,

Bank of England, Bank of Canada and Swiss National Bank. These are unlimited,

so are valued at their one-way maximum historical usage. This group covers

all issuers of currencies individually identified in the IMF's reserve

currency composition database except for Australia and China

Sources: central bank websites; news sources; RBA |

|||

Regional financing arrangements

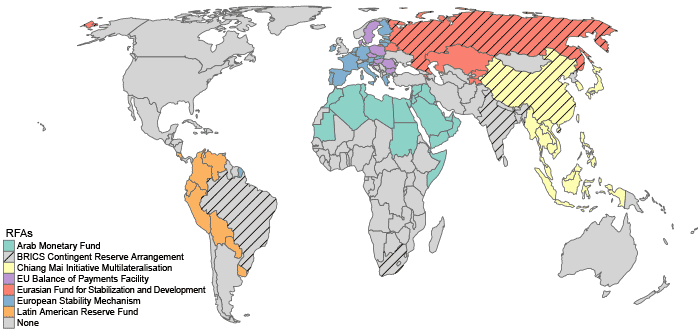

Total RFA lending capacity amounts to US$1.0 trillion, which is similar in magnitude to IMF resources. Access to RFAs varies significantly across regions, with many countries having no access to RFA financing (Figure 2). Together, the two largest RFAs (European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralisation (CMIM)) account for over 80 per cent of the value of RFA funds. The ESM has total lending capacity worth €500 billion, equivalent to over 4 per cent of euro area GDP, and is available to euro area countries experiencing financing difficulties. The CMIM, comprising US$240 billion of commitments, was set up to address members' BoP and short-term liquidity difficulties and complement existing financial arrangements. Like swap lines, some RFAs (including CMIM) have not yet been used, and are therefore untested in an active crisis.

Sources: RBA; RFA websites

Recent Developments

Enhancements to the GFSN

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to developments in both access to the GFSN and its size. Starting with the IMF, the organisation has announced significant changes to its lending facilities to provide support during the crisis. These changes cover:

- Access. The IMF clarified early in the crisis that countries hit by the pandemic would be eligible for its emergency facilities, which gave countries more certainty in their ability to access this class of assistance. The IMF has also temporarily increased its lending limits to individual members, including the access limits for its emergency facilities and its overall annual lending limits, as well as increased the number of times that countries can access certain emergency facilities.

- New Facility. The IMF also introduced a new precautionary facility – the Short-term Liquidity Line – which is designed to provide liquidity to countries with ‘very strong policy frameworks and fundamentals’ that have short-term liquidity needs as a result of an external shock (IMF 2020b). This supplements existing precautionary facilities.

- Increased Funding. In addition, the IMF secured increased funding for its concessional financing of low-income countries through its Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust, including an in-principle SDR500 million commitment from the Australian Government.

Also, IMF and RFA cooperation has increased during the COVID-19 crisis. This has included an increased and more regular exchange of information between these two layers of the GFSN (G20 2020), and, in June 2020, the amendment of the CMIM agreement to strengthen its coordination and better align its lending facilities with the IMF. This builds on significant efforts in recent years to enhance coordination between the IMF and the RFAs, which has included undertaking simulations of joint programs, high-level dialogues, and building on G20-endorsed principles to guide cooperation between the IMF and RFAs (IMF 2017).

The number of BSAs has increased since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (Graph 5). The US Federal Reserve has temporarily extended its existing US dollar swap lines to a number of additional central banks from both advanced economies and EMEs, including the Reserve Bank of Australia. In addition, it has established a temporary facility that allows foreign central banks to borrow US dollars by providing US Treasury securities as collateral (Federal Reserve 2020). This facility is aimed at supporting the functioning of the US Treasuries market, but it also has the effect of supporting US dollar liquidity globally. Indeed, the new and existing Federal Reserve measures have been important in decreasing disruptions in US dollar cross-border funding markets and more broadly supporting confidence in global financial markets (Avdjiev, Eren and McGuire 2020). The European Central Bank has introduced a similar facility, aimed at providing euro liquidity to limit market dysfunction (European Central Bank 2020).[14] They also established BSAs with several other European central banks.

Use of the GFSN

So far, the GFSN has played a significant role in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, use has varied significantly across countries and layers.

The IMF has played a central role in assisting countries in need of BoP support in recent months, in particular to help fund the additional health care spending required in some countries. By number, the primary form of assistance has been emergency facilities that can be quickly paid out and do not come with conditions that must be met after the funds have been provided. So far the IMF has approved 74 emergency facilities in response to the pandemic (Graph 6), as well as increased the funding limits of some existing programs. Apart from a few exceptions, emergency financing has mostly been provided to small EMEs and low-income countries. This, combined with the lower access limits of emergency facilities, has meant that the total value of these facilities has been modest.

The few large EMEs to draw on IMF emergency financing so far include South Africa, Nigeria, Pakistan and Egypt, which have each been granted lending to support spending on health and address the economic impact of the crisis. New IMF programs were also approved for Ukraine and Egypt, with the impact of the pandemic adding to existing challenges.

In addition, Chile and Peru have joined Colombia and Mexico in requesting access to the IMF's Flexible Credit Line, one of the IMF's precautionary facilities that allow countries with very strong fundamentals and policy track records to draw on IMF funding at any time should a crisis emerge. By value these account for the majority of funds committed by the IMF in recent months. However, these precautionary facilities are for potential rather than existing BoP needs, and to date have not been drawn down.

One reason that most large EMEs have not drawn on IMF support is that they have not needed it. The initial market disruption caused by the pandemic in March eased relatively quickly following the unprecedented policy responses in both advanced economies and EMEs, including the introduction of swap lines (see below). These actions, in effect, supported external financing conditions for many EMEs. In addition, many EMEs, especially in the Asia Pacific region, entered the pandemic with strong fundamentals and large precautionary reserves (IMF 2020c). Furthermore, in many countries in the region, the proactive relief policies and lockdowns implemented by policymakers supported market confidence.

Central bank swap lines have played a key role in the response to COVID-19, specifically by reducing disruptions in cross-border financial markets and thereby contributing to the easing in emerging market financial conditions. Swap lines with the Federal Reserve have been used in large volumes since March (Graph 7). Even while some of the lines have not yet been used, their existence has supported confidence in those countries' markets.

A number of EMEs also used their reserve holdings to intervene in the foreign exchange market in March when markets were most volatile. This intervention was used to counter large depreciations in some currencies and reduce excessive volatility. The pace of intervention declined once volatility in market conditions subsided.

There has been little usage of any RFAs to date. The Arab Monetary Fund and Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development appear to be the only RFAs that have extended loans to some members since March. This is partly because the countries with the most access to RFAs have generally not experienced BoP difficulties beyond the initial turbulence in March and April. They also typically have larger IMF access limits, and are more likely to be able to access swap lines or other sources of support. The majority of countries that have applied for IMF emergency lending are those that are not members of an RFA.

The GFSN and the RBA

Australia participates in three layers of the GFSN: it is a member of the IMF; has a range of central bank BSAs; and it holds reserves.

As a member of the IMF, Australia contributes funds to support its lending. The total funding is worth SDR13.4 billion, comprising of a paid-in (quota) contribution worth SDR6.6 billion and a further SDR6.8 billion pledged under the New Arrangements to Borrow and Bilateral Borrowing Agreement arrangements (Graph 8). Australia has also recently committed, in principle, an extra SDR500 million to support concessional lending by the IMF. It is important to note that this is the maximum possible financial commitment of Australia to the IMF, with the borrowing arrangements only drawn on as required.

The rights and obligations associated with Australia's membership of the IMF are vested with the Australian Government. This means that Australia's contributions to the IMF are funded out of the government's revenue. The Reserve Bank acts as the banker for transactions between the IMF and the Australian Government, and will sell foreign currency to the government for it to make these transactions.[15] Although these transactions have implications for the Reserve Bank's balance sheet, the historically small size of IMF transactions means that these transactions generally have not materially affected the Reserve Bank's reserve holdings or balance sheet.

The RBA also has five swap line arrangements with foreign central banks (Table 3). The largest of these is the arrangement with the Federal Reserve, which was originally established following the GFC and re-established earlier this year. Under this arrangement the RBA makes US dollars available to eligible Australian market participants. However, in line with modest demand for US dollar funding, this has had minimal usage (Reserve Bank of Australia 2020). The purpose of the other swap lines varies by counterparty, but the reasons are broadly to support trade and investment, local currency settlement and financial stability. Not all of these swap lines can be considered part of the GFSN; in some cases their attributes – such as not being denominated in a reserve currency – may materially limit their scope to address the types of crises on which the GFSN is focused.

| Counterparty central bank |

Size

A$ billion |

Established | Stated purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| People's Bank of China | 40(a) | 2012 (renewed 2015, 2018) | Support trade and investment; strengthen financial cooperation |

| Bank of Korea | 12(b) | 2014 (renewed 2017, 2020) | Promote trade; enhance financial stability; other mutually agreed purposes |

| Bank Indonesia | 10 | 2015 (renewed 2018) | Promote trade; enable currency settlement during times of financial stress |

| Bank of Japan | 20 | 2016 (renewed 2019) | Enhance financial stability |

| US Federal Reserve | US$60 billion | 2020 (previously established in 2008 and expired in 2010) | Foreign currency liquidity |

|

(a) Originally agreed for A$30 billion; increased to A$40 billion in 2015

Source: RBA |

|||

The Reserve Bank also holds the bulk of Australia's official reserve assets on its balance sheet. Specifically, the Reserve Bank owns and manages Australia's gold, SDR and foreign exchange holdings (Vallence 2012). The Australian Government holds the only other component of Australia's official reserve assets – the reserve position with the IMF. This portion is held on the government's balance sheet since Australia's membership of the IMF is vested with the government.

Conclusion and Looking Ahead

The GFSN has played an important role in the official sector response to the COVID-19 pandemic, together with other policy measures by central banks and fiscal authorities. So far, the IMF's response has included the provision of funding for EMEs and low-income countries to address their BoP problems and support spending on health. Central bank swap lines have also helped a range of countries by addressing stresses in cross-border funding markets. More broadly, the existence of the GFSN has played a stabilising effect by providing confidence that countries have a backstop if they experience a crisis.

The GFSN has considerable scope to provide further support. Most large EMEs continue to have sizable reserve buffers, and so far only one-quarter of the IMF's resources has been lent or committed to being lent. Many swap lines have not been used, and those that have been used have generally not reached limits, and RFAs have largely not yet been called upon.[16]

This notwithstanding, the synchronised nature of the current crisis and the highly uncertain outlook mean that there could be very large calls on the GFSN over the period ahead. This is particularly the case if downside risks to the health and economic outlook materialise. This could see demand for resources from previously untested parts of the GFSN, such as RFAs and some government endorsed or sponsored swap lines. It may also see more coordinated use of the different layers of the GFSN. The GFSN itself may also evolve further as countries respond to collective challenges and work together to promote the stability of the global financial system.

Appendix A

| Purpose | Cumulative Limit | Eligibility(b) | Conditionality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency | ||||

| Rapid Financing Instrument | Help countries facing urgent BoP needs | 100 per cent of quota (temporarily increased during COVID-19 to 150 per cent of quota) | All members | None after funds are provided, although the country is expected to cooperate with the IMF to resolve BoP issues |

| Standard | ||||

| Stand-by Arrangement | Help countries facing BoP needs, and provide support for adjustment policies | 435 per cent of quota(c) | All members | Yes |

| Extended Fund Facility | Help countries facing long-term BoP needs, and provide extended support for policies to correct structural problems | 435 per cent of quota(c) | All members | Yes |

| Precautionary | ||||

| Precautionary Liquidity Line | Meet liquidity needs | 500 per cent of quota | Members with sound economic fundamentals | Yes |

| Flexible Credit Line | Provide backstop funds in event of a crisis | Case-by-case assessment | Members with very strong economic fundamentals | None |

| Short-term Liquidity Line | Meet liquidity needs due to external shocks | 145 per cent of quota (annual) | Members with very strong economic fundamentals | None |

|

(a) Non-concessional facilities only; there are equivalent concessional facilities

for standard and emergency facilities

Sources: IMF; RBA |

||||

Footnotes

Meika Ball and Clare Noone are from International Department, and Ashwin Clarke contributed to this work while in International Department. We would like to thank Anna Park, Rosa Bishop and David Lancaster for their comments and assistance. [*]

While multilateral development banks, for example the World Bank, have provided important financial assistance to support countries' responses to the pandemic, these institutions are not technically part of the GFSN since the funding they provide is typically targeted at specific needs, rather than general support for balance of payments or sovereign debt difficulties. [1]

SDRs are an international reserve asset that can be used as a claim on currencies held by IMF member countries. They were created by the IMF to supplement member countries' existing reserves, and are valued as a basket of major currencies. [2]

Swap lines can also be directly between two finance ministries, but these are generally not considered part of the GFSN (due to their different purposes) and so are excluded from the analysis undertaken in this article. [3]

We assess that swap lines backed by governments are more likely to be utilised in a broader range of crises as a form of bilateral cooperation. The written purpose of these swap lines can be very varied, and there is some evidence of their use in different crises. Similarly, swap lines issued by the PBC have been used to address a range of crises, including BoP crises. Both Pakistan in 2014 and Argentina in 2015 drew on their PBC swap lines to bolster their reserves and avoid a currency crisis. While both countries borrowed local currency (RMB) under their respective swap line, they were able to convert the funds to USD in the offshore RMB market (Li 2015). [4]

See Vallence (2012) for more detail. [5]

There could be domestic opposition to this. There can also be stigma associated with an IMF loan: foreign investors may interpret an IMF program as signalling that the country is facing bigger challenges than expected (Ito 2012). [6]

This has increased from around 8 per cent of world GDP in 2000. Given that a number of swap lines are only available for an FX liquidity crisis, the total lending capacity of the GFSN is a little less than this for other crises. There is some double counting in calculating the overall size of the GFSN, since countries' FX reserves fund various parts of the GFSN. [7]

PBC swap lines are assumed to automatically renew (given data inconsistencies). Unlimited swap lines are assigned a potential value equivalent to the historical maximum. Data for Latin American Reserve Fund not available prior to 2008. Includes IMF liquidity buffer. [8]

The IMF adequacy metric assesses the ratio of reserves available to a weighted average of resources required to cover three months of imports, 20 per cent of broad money, and total short-term debt (IMF 2015). [9]

There are two types of lending arrangements: a common multilateral arrangement that has been signed by a number of countries, called the New Arrangements to Borrow; and a range of Bilateral Borrowing Agreements. [10]

Although commitments have not changed since 2012, the total value of commitments has varied in line with exchange rate movements. [11]

Changes to quota have been implemented periodically, but this misalignment still exists. This constraint is mitigated to an extent by the IMF's exceptional access framework, which allows the Fund to extend lending above limits under specific circumstances. For instance, during the European debt crisis, when large lending programs were provided to Greece, Ireland and Portugal (Edwards and Hsieh 2011). [12]

Comoros (member of the Arab Monetary Fund) and Malta (member of the ESM) not shown

on map.

For a list of members: Arab Monetary Fund,

BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement,

Chiang−Mai Initiative Multilateralisation,

European Stability Mechanism,

EU Balance of Payments Facility (EU countries not in the ESM),

Eurasian Fund for Stabilization and Development,

Latin American Reserve Fund.

[13]

It is debateable whether the central bank repurchase facilities of the Federal Reserve and European Central Bank should be considered part of the GFSN. While they do help countries address foreign currency liquidity shortages, this is not their only objective. Moreover, a country has to use its foreign exchange reserves (specifically, the country's official holdings of US or European government securities) to access these facilities. Including them in our analysis would therefore lead to substantial double counting when calculating the size of the GFSN. For this reason they are not included in our analysis of the size of the GFSN. [14]

Poole (2012) provides more detail on the interaction between IMF transactions and the RBA's balance sheet. [15]

Indeed, the swap lines that have been used the most in recent months are for an unlimited value in theory. [16]

References

Avdjiev S, E Eren and P McGuire (2020), ‘Dollar funding costs during the Covid-19 crisis through the lens of the FX swap market’, BIS Bulletin No 1, 1 April.

Denbee E, C Jung and F Paternò (2016), ‘Stitching together the global financial safety net’, Bank of England Financial Stability Paper No. 36, 12 February.

Edwards K and W Hsieh (2011), ‘Recent Changes in IMF Lending’, RBA Bulletin, December, pp 77–82.

European Central Bank (2020), ‘New Eurosystem repo facility to provide euro liquidity to non-euro area central banks’, Press Release, 25 June.

Federal Reserve (2020), ‘Federal Reserve announces establishment of a temporary FIMA Repo Facility to help support the smooth functioning of financial markets’, Press Release, 31 March.

G20 (2020), ‘Communiqué’, G20 Finance Ministers & Central Bank Governors Meeting, 18 July.

IMF (2015), ‘Assessing Reserve Adequacy - Specific Proposals’, April.

IMF (2017), ‘Collaboration between Regional Financing Arrangements and the IMF’, IMF Policy Paper, 31 July.

IMF (2020a), ‘IMF Factsheets: IMF Lending’, International Monetary Fund site, 27 March. Available at <https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/IMF-Lending>.

IMF (2020b), ‘IMF Factsheets: Short-term Liquidity Line (SLL)’, International Monetary Fund site, 22 April. Available at <https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2020/04/17/short-term-liquidity-line>.

IMF (2020c), ‘Transcript of April 2020 Asia and Pacific Department Press Briefing’, International Monetary Fund site, 15 April. Available at <https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/04/16/tr041520-transcript-of-april-2020-asia-and-pacific-department-press-briefing>.

Ito T (2012), ‘Can Asia Overcome the IMF Stigma?’, American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 2012, 102(3), pp 198–202.

Li C (2015), ‘Banking on China through Currency Swap Agreements’ Pacific Exchange Blog, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco site, 23 October. Available at <https://www.frbsf.org/banking/asia-program/pacific-exchange-blog/banking-on-china-renminbi-currency-swap-agreements/>.

Poole E (2012), ‘Australia's Financial Relationship with the International Monetary Fund’, RBA Bulletin, December, pp 65–71.

Reserve Bank of Australia (2020), ‘International Financial Conditions’, Statement on Monetary Policy, May, pp 19–30.

Stevens G (2007), ‘The Asian Crisis: A Retrospective’, Address to The Anika Foundation Luncheon, Sydney, 18 July.

Vallence C (2012), ‘Foreign Exchange Reserves and the Reserve Bank's Balance Sheet’, RBA Bulletin, December, pp 57–64.