Speech Some Observations on the Current International Conjuncture

Glenn Stevens

Assistant Governor (Economic)

CEDA/Telstra Economic and Political Overview

Sydney/Melbourne – –

Thank you to CEDA for the invitation to be here once again, carrying on a long tradition of these January addresses on the economic outlook.

I want to begin by inviting you to recall the situation as it was a year ago. In January 1998:

- the "crisis" economies of east Asia were well into a period of savage adjustment. This was characterised by withdrawal of foreign capital, intense pressure on financial markets and institutions, which was being countered by much tighter macroeconomic policies, sharp contractions in economic activity, and trade balances moving dramatically to surplus, mainly due to a collapse in imports. For Thailand, Korea and Indonesia, January 1998 was the period of most intense pressure on their currencies and financial markets. Policy makers in major countries were just starting at that time to give the Asian crisis the attention it deserved;

- the bulk of observers were beginning to realise – belatedly – that Japan had gone into recession in the middle of 1997;

- the United States economy looked robust, growing faster than it could likely sustain in the long run, and it was a widespread view that growth in the US needed to, and would, decline. The US share market seemed high by most conventional valuations (the Dow was 7800); and

- Europe was pre-occupied in preparation for the Euro.

At that time, we would have had good grounds for suspecting that the year ahead was going to be very difficult, particularly for Australia. Events in 1998 which few people would have predicted included:

- the intensity and scale of speculative activity in international markets in mid year, which, amongst other things, put intense pressure on Hong Kong financial arrangements (and the Australian dollar);

- the default by Russia in August, which was the proximate trigger for a large-scale re-assessment of risk by internationally-active investors, which affected Latin America;

- the failure and subsequent rescue of a prestigious US hedge fund; and

- the extent to which those events affected liquidity and prices in the deepest of capital and foreign exchange markets, including in the United States.

In short, 1998 was a year of extreme financial instability.

People were also perhaps ill-prepared for the difficulty in achieving concrete progress in addressing the deep-seated problems in Japan, which became one of the major issues for the world economy during 1998.

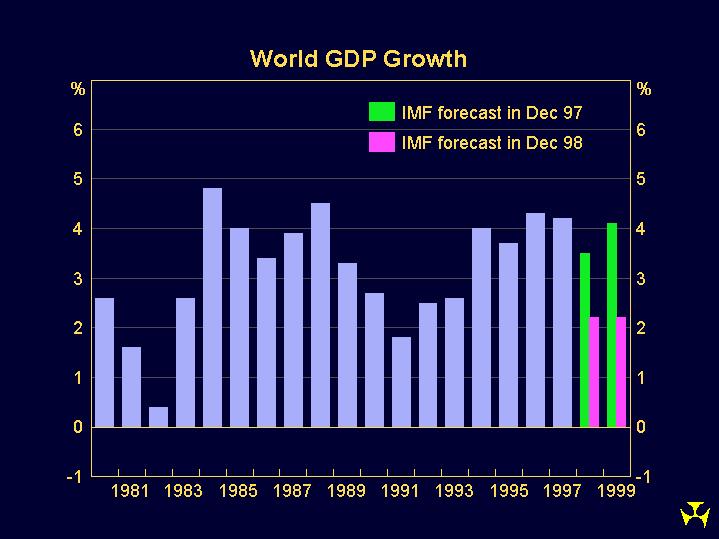

As the year went on, more people began to talk about global recession. Yet global recession has not occurred, if by that term we mean the bulk of the industrial countries going into more or less simultaneous downturn. 1998 was certainly a very weak year for global growth, but it did not see a downturn in activity everywhere, with both Europe and the United States continuing to expand. In fact, 1998 was yet another year of exceptionally good growth for the US economy. And, of course, contrary to the expectations of many commentators a year ago, it was a very good year for the Australian economy.

So how do things look in January 1999? I would offer six observations here.

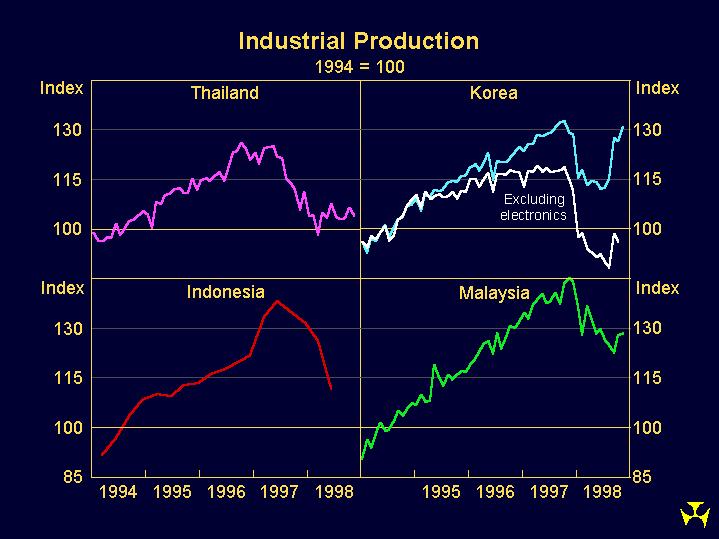

First, the adjustment in east Asia is continuing, and has now reached a different stage. It is reasonably clear that economic activity in Thailand and Korea found bottom during 1998. (For Indonesia, the evidence is much less clear.) At the same time, several other countries around Asia which were not part of the initial currency and banking crisis itself have gone into recession, or are at best enjoying much reduced growth. Hong Kong and Singapore are two cases in point.

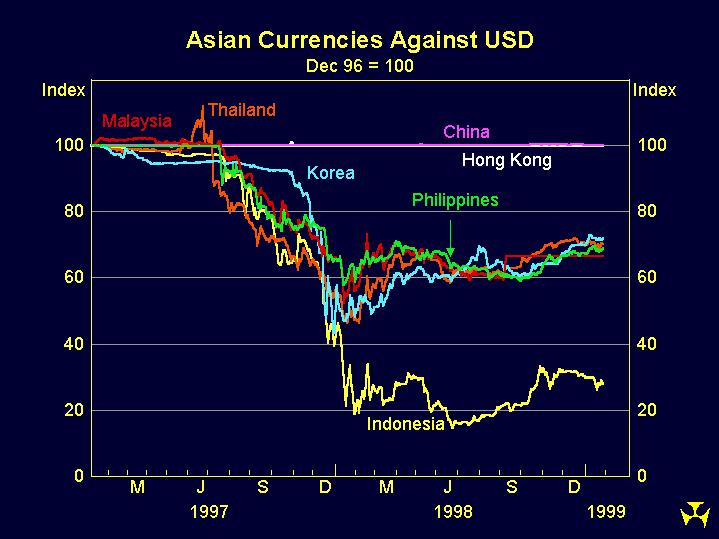

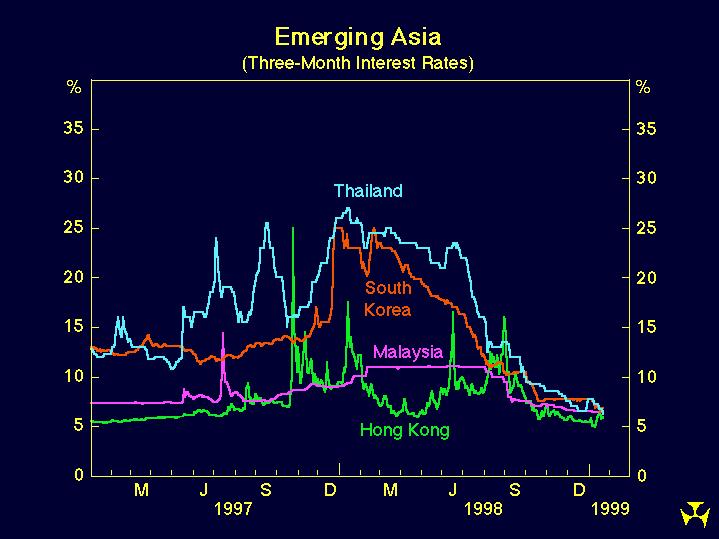

In the year ahead, it is not unreasonable to think that the beginnings of new growth will be seen in several of these countries. Interest rates in most cases have fallen back to levels lower than those which prevailed prior to the crisis. Budgetary policies are being pushed in the direction of expansion. The all-pervasive sense of crisis on Asian currency markets seems to have passed, and most Asian currencies have in fact recovered ground. In a few cases, some foreign capital has – cautiously – flowed back in. (Lower interest rates in the United States and a lower US dollar have helped considerably here.) Growth will be hesitant and rather sluggish overall in the crisis countries I think – they still have a lot of work to do in fixing financial and corporate sectors. Nor, I suspect, is growth ever likely to be as fast and as sustained as it was in the early 1990s in Asia. But the east Asian countries are, in my judgement, reaching a point where the most likely outcome over the next twelve months is the emergence of tentative expansion, rather than further contraction. (Indonesia, again, is a case where one can be far less confident about the outlook.) Indeed, I think it might be said that the region about which uncertainty regarding economic prospects is greatest is no longer Asia, but Latin America, and it is noteworthy that the Asian financial markets came through the rounds of international instability in the latter part of 1998, and the recent Brazilian crisis, without serious mishap.

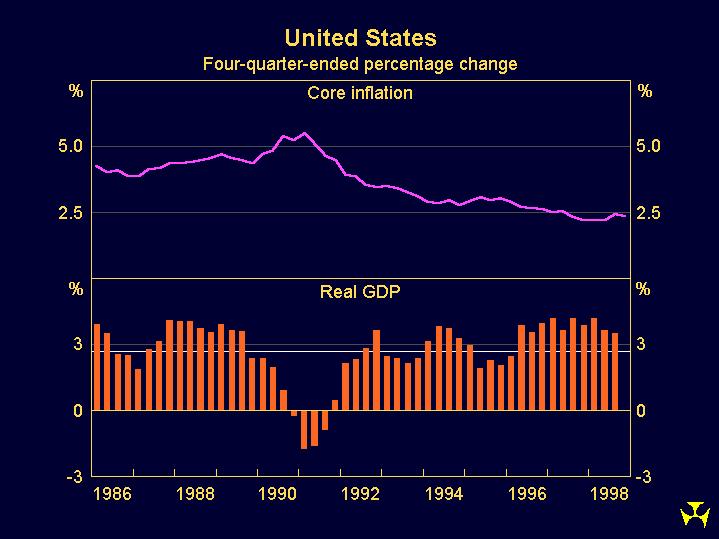

My second observation is that the US economy still – remarkably – looks strong. By end 1998, the US had chalked up almost eight years of expansion, with five of those eight years, and each of the past three years, characterised by growth in the range of 3-4 per cent – this in an economy whose long-run trend rate of growth is thought to be about 2 ½ per cent. It was recently pointed out that not only is the current upswing in the US economy the longest expansion since the 1960s, but that it follows hard on the heels of the second longest. For 15 years now, the US has enjoyed good growth, punctuated by what was really a fairly mild recession in 1990. Confidence amongst Americans in the prospects for the US economy has remained strong. The only area which has really shown any sign of the long-foreshadowed slowdown is manufacturing, which has been hit by lost export sales and heightened competition from imports. In most other areas, the US economy remains quite strong.

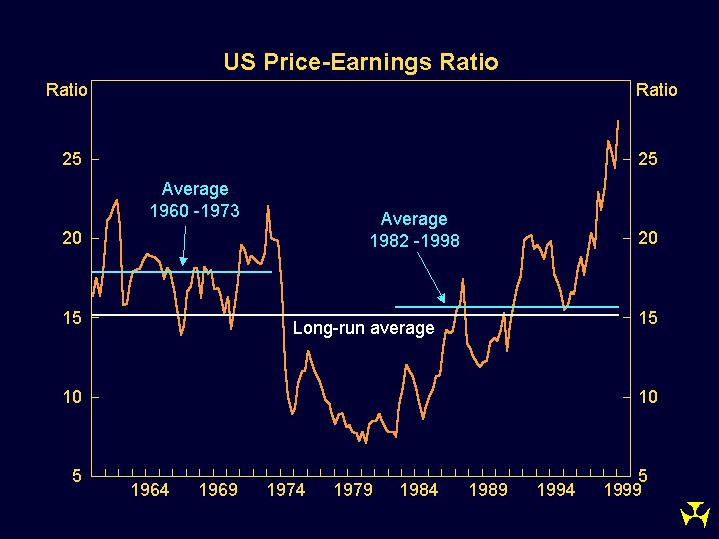

Yet despite this prolonged period of well above average growth, there has been very little pick-up in inflation – indeed inflation has fallen a bit over recent years. This has kept interest rates generally low, which has assisted with capital formation, which has in turn helped to keep the expansion in demand going and also added to the economy's supply capacity. The US share market has continued its climb – albeit with a serious fright in October – and has reached levels which stretch the imagination in terms of conventional ways of valuing the market.

Much discussion has taken place over whether all this represents a "new paradigm". There is clearly something new, though the more optimistic participants in this debate tend to neglect or downplay some temporary features which have helped US macro economic performance. One is the fact that the US economy has been able to draw on spare capacity globally, which is helping to keep prices low (a high US dollar was part of what helped this adjustment come about, for a while at least). There are other partial explanations which also make the performance slightly less miraculous. But there is no doubt that US economic performance, even if not miraculous, is certainly impressive.

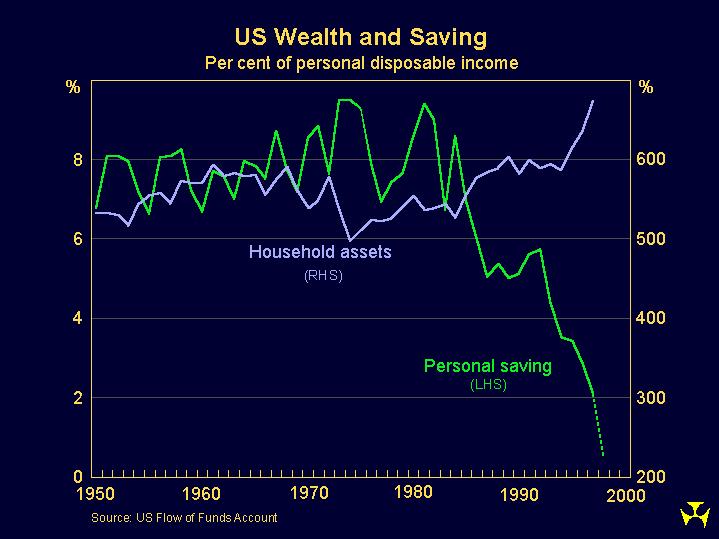

One intriguing development in all this is that the US household saving rate as measured is now zero or even negative. That is, US households are consuming in aggregate an amount at least equal to their total measured income. What is going on here? There are some technical reasons why saving is understated in the data, but the main answer seems to be that the wealth of households has risen, as a result of the share market boom, to such levels that there really is a widespread wealth effect. In essence, it might be said that the share market valuations imply substantial gains in future income for the owners of corporate assets – perhaps because of confidence in a "new paradigm" – and that some of that income is being consumed now. For the United States in aggregate to do this, of course, requires a higher current account deficit – domestic absorption rises relative to current income. And the trade counterpart to this is the loss of exports and higher imports due to the Asian crisis and other international developments.

A risk in all this has been pointed out by many commentators: if the share market declined sharply, for whatever reason, then (assuming the above characterisation of behaviour is correct) households might contract their expenditure abruptly, leading to a sharp downturn in economic activity. It would be foolhardy to pretend to know the course of stock prices, so I will not dwell on this risk. It is worth observing, however, that had such a slump occurred in 1998, at a time of turmoil and uncertainty internationally, it might have been very damaging for the world economy. As it was, the buoyancy of the US economy through the past year gave the rest of the world time to make progress against other difficulties. Another risk, of course, is that the US emerges from this episode with an overheated domestic economy.

A third feature at present is that the Euro has arrived, and without any significant hiccups so far. As part of this process, interest rates in Europe have converged down to the low levels of France and Germany, which has imparted a mild expansionary element to European monetary policy as a whole. 1998 was a reasonable, if not brilliant, year for Europe on growth even though there is a legacy of earlier weak growth which has left unemployment rates very high. Inflation in Europe – as in most places – is exceptionally low.

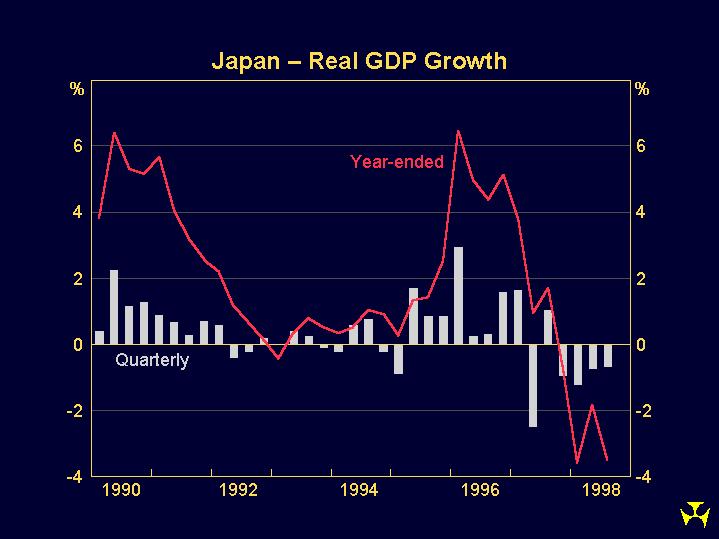

My fourth observation is that Japan is still in recession on the most recent data, and over the past year and a half has recorded what has to be its worst economic performance in half a century at least. If there is one country which looks to be in deflation and depression-like circumstances, it is Japan. Economic activity has been falling, prices declining, credit getting more restrictive, confidence at a low ebb, and unemployment rising.

The Japanese authorities have a three-pronged strategy in trying to turn this around: extremely low interest rates, fiscal expansion and banking sector reform. How effective is this likely to be? The honest answer is that this is very unclear. In conditions of deflation, banks being reluctant to lend and borrowers possibly equally reluctant, low interest rates – while clearly appropriate – are not as effective as at other times. Fiscal policy is effective and we have seen for several months now the first signs that the increased spending on public works is affecting the construction sector. The problem is that this expansion is pushing into a fairly strong headwind. And getting progress on fixing the banking system has been slow. So it is easy at this stage to get very pessimistic about Japan because policies haven't seemed to work so far. There is also a tendency for commentators to criticise new measures as inadequate; almost whatever the authorities do, it is not enough for those who have tired of waiting for results.

However, the fiscal stimulus is starting to work, as I noted above. I also detect an increasing tendency for those involved in the financial restructuring from the public sector side in Japan to act more aggressively; this is welcome. Hence, while the short-term outlook for Japan is anything but rosy – the optimists expect growth of just over zero in 1999 – this year the policies may succeed in establishing a better platform for growth.

A fifth feature of the current environment is the talk of over-capacity in a number of global industries – such as steel, automobiles, oil and various other commodities, airline seats, financial services. As a result, there is tremendous discipline on prices for traded goods and services, and remarkably low inflation generally. There is also, not unrelated to these price trends, a trend towards rationalisation, often via mergers of unprecedented size.

A view we sometimes hear is that this is as a result of the Asian crisis, with Asian countries flooding world markets in order to gather export revenues. I think it is not quite so simple. The Asian crisis has played a role, though a rather more complex one, and there are other things going on too. The trend towards excess capacity in areas like automobiles has been driven in part by the rapid expansion by some Asian countries like Korea, but that was happening before the Asian crisis hit, and was in a very real sense one of the causes of the crisis for some of the countries concerned, more so than a consequence. The depreciation of Asian currencies has conferred a short-term competitive advantage on Asian producers, but then they are battling with other problems like dysfunctional financial systems in their own countries, and higher costs for capital and imported components. Exports from Korea have expanded rapidly, but that trend also predates the onset of the crisis. And evidence of a "flood" of exports from other Asian countries is actually far from clear in the data. At least as important as the export efforts by Asian countries has been the collapse in domestic demand in these countries. As an example, the value of the fall in imports into Korea over the past year is twice as large as the rise in their exports; the fall in total domestic demand was four times larger than the rise in exports. Even more important has been the retrenchment of domestic demand in Japan, which is about as large in the world economy as all the countries of east Asia combined.

Generally speaking, demand in a significant part of the world is unusually low. In one (important) case, the United States, demand is strong. It may be running ahead of that economy's supply capacity, though the extent of that is uncertain. What is reasonably clear, however, is that the US is the only major part of the world for which it could be said that demand is near capacity. In Europe, domestic demand is growing, but could probably grow strongly for a while yet before capacity constraints would bind. And in Asia and Japan, as I noted above, demand is far below the respective supply capacity of the economies concerned. In aggregate, global demand has been growing because the US and Europe have expanded by enough to more than offset the contractions elsewhere but more slowly than global capacity. So the world's "output gap" has been increasing (this was nicely illustrated in some charts in the OECD's December 1998 Outlook.) This situation is why, even though there is not a global recession in the sense of a contraction in activity everywhere, there is a lack of what business people refer to as "pricing power". And it is why interest rates in most countries have been tending to decline.

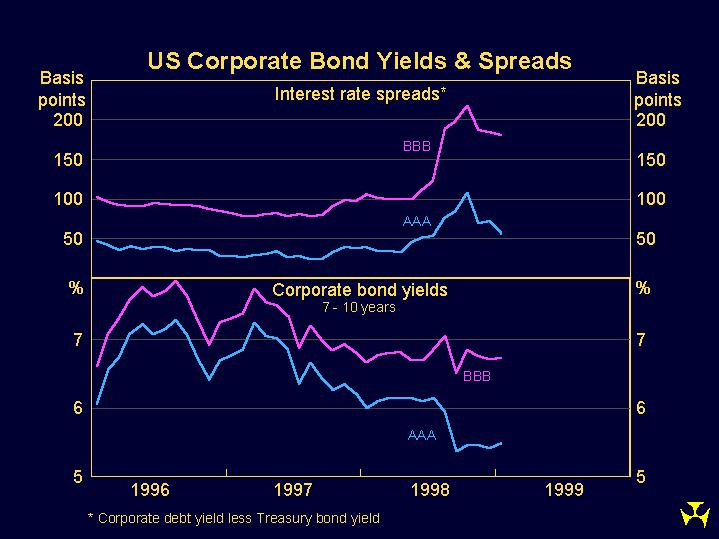

This brings me to my final observation, which is about financial markets. We see at the present juncture a more cautious attitude to risk amongst financial institutions. This was exemplified in the abrupt turnaround in capital flows to emerging markets which began in 1997, but also took the form of higher pricing for risk, via a widening of credit spreads, across a range of markets. The latter was most pronounced for emerging market borrowers but was also evident late in 1998 even for reasonable quality borrowers in the United States. These higher spreads and a sharp reduction in liquidity were important factors prompting three easings of US monetary policy late last year. These helped calm markets down.

A more sober assessment of risk is, to a point, probably welcome as a longer-run trend, even though it might have had some temporary disruptive effects. My main point, however, and to my surprise few commentators seem to mention this, is that even with higher spreads the absolute cost of borrowing for many reasonable quality borrowers in US and European markets is no higher – and is probably lower – than it was two or three years ago. Interest rates and the cost of capital generally are low on a global basis, and this has to be an expansionary factor for global growth.

What then of prospects for 1999?

As we look at forecasts prepared by international forecasters, we have seen a succession of downgrades for global growth over the past year. Those resulted from forecasters taking on board the fact that they had underestimated the severity of the contractions in east Asia, and the virulence of the recessionary forces at work in Japan. A number also became quite pessimistic about the US, at the height of concerns about the possibility of a "credit crunch" around October last year.

My guess is that forecasts for most of the east Asian countries are probably reaching the end of the phase of downward revision. As I said earlier, it seems to me that the gradual emergence of growth is more likely than further contraction this year in most cases. There is a long way to go in fully recovering from the crisis and it will take many years, but we have, I think, reached the end of the beginning.

Most forecasters continue to expect a slowing in the US economy. Eventually, this has to be right but it's been wrong for a few years now. With recent US data strong, consensus opinion is probably swinging away from the idea of a hard landing/possible recession scenario in the US, in favour of something more benign. The main risk people point to is the possibility of a share market decline. (The question would then be what triggers that event.) Expectations for Europe seem to be for continued gradual growth, though just now these are not quite as confident as they were a few months ago, because recent data have been a bit on the soft side.

The part of the global growth equation which is most likely to be subject to downward revision may be Latin America. My basis for saying this is that the air of crisis over Brazil in recent months has led to higher interest rates around the region, and which will have a bearing on economic outcomes. Already there are clear signs of weaker activity in the large south American economies. Australia's direct trade with Latin America is not that big but the region's importance looms larger because of its proximity to the United States and the attention it receives in Washington and Wall Street.

The most uncertain part of the outlook internationally, however, remains Japan. It is being assumed by most forecasters that 1999 will not see as big a contraction in output as 1998. I think that is the best presumption to make, but it is noteworthy that forecasts have continued to be revised down over recent months. Realistically, we cannot hold any forecast about Japan with much confidence.

What does all this mean for Australia?

A year ago, the main question on most lips for Australia was the extent to which lost sales in Asia would affect exports and hence economic growth. As things have turned out, and this is well-documented in many places, including the Bank's publications, the loss of sales to the crisis countries in Asia was quite substantial, but was partly offset by gains in other markets, particularly the United States, Europe and several other smaller and less traditional markets. Diversion was particularly pronounced for resources. The decline in the exchange rate no doubt gave some assistance to this process.

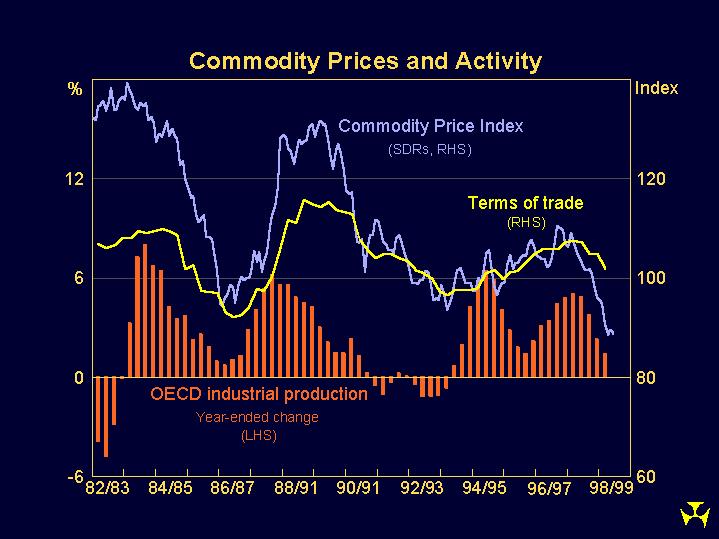

Over recent months, we have seen effects on the prices (in foreign currency terms) of many of our commodity exports, and ongoing pressure on resource producers to adapt to those changes.

In January 1998, commodity prices had fallen by 5 per cent from their mid 1997 lows; by January 1999, they had fallen a further 13 per cent. The excess supply is at least partly cyclical, with OECD industrial production growth declining sharply over the past year, mainly reflecting the weakness in Japan and the slowdown in industrial production growth in the US.

Australia's terms of trade have fallen since mid 1997 by about 9 per cent. Some further falls seem likely in the short term. While this is a considerably smaller fall than has occurred on some other occasions in history, it is nonetheless a significant loss of income to Australians. It is one of the principal reasons behind the common view that growth in Australia is likely to be somewhat lower over the coming year than it was in 1997 and 1998. I will leave a more detailed discussion of the Australian situation to the other speaker.